The people here danced to the tune of Moscow‘s whistle

Stáhnout obrázek

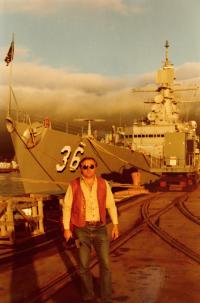

Zdeněk Hostaša was born on 15 June 1935 in Hranice na Moravě, the first child of a local fruit merchant. The witness‘s father was active in the anti-fascist resistance in the so-called Paváz Group, but he was caught and deported to Auschwitz, where he was shot in 1941. In the early 1950s Zdeněk began working for a steamboat company. He took part in a trip to West Germany and gained experience from a non-communist country. However, after various conflicts with his employer he lost his job of cabin boy after less than a year. He tried several jobs, working as a locksmith, miner, or manual labourer. In 1953 he attempted to cross the border into Austria, but failed to escape. He was successful two years later, when he first crossed over into East Germany and from there into West Berlin. He stayed in several refugee camps and accepted the offer to become an agent of the American secret service CIC. His reward for fulfilling his tasks was to be the permission to emigrate to the US. After six months training Zdeněk was sent into Czechoslovak territory under a false identity. However, he was arrested on 13 May 1956 when making contact with an informant in Prague. He was stood before a military trial in Trenčín and sentenced to twenty years of prison. He spent time in the former fortress of Leopoldov, where he met with important political prisoners, for example the bishop Jan Anastáz Opasek. After an amendment to the law in 1964 he was released with a twenty-year long parole period. He took up mining again, working in Ostrava. The invasion of the Warsaw Pact armies in 1968 was an impulse for Zdeněk to attempt another escape. He did so in September of the same year together with a former co-prisoner from Leopoldov and his brother. The crossing from South Moravia to Austria was difficult, only Zdeněk managed to escape, his colleagues were arrested by the Border Guard. Zdeněk went through another round of refugee camps in Austria, where he was joined by his wife and children. Together they emigrated to Chile, where they spent three years. In 1971 they moved to Texas, where Zdeněk Hostaša worked as a petrol pump assistant and then a welder for nuclear reactors. Following November 1989, he and his wife returned to their homeland.