It‘s easy to blame everything on the regime but one must question oneself too

Stáhnout obrázek

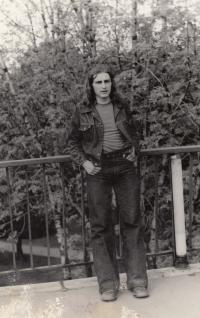

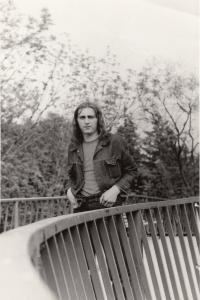

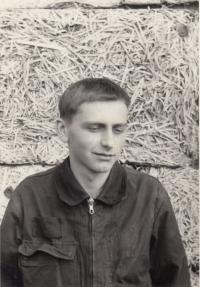

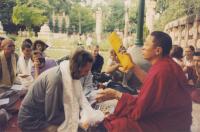

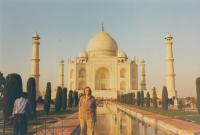

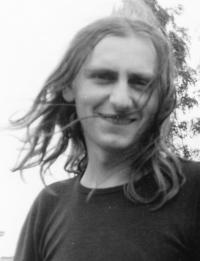

Jiří Holba was born on May 11, 1953, in Vsetín and grew up with his mother and grandfather in Bystřička, Vsetín region. He trained to be an electro-mechanic, in 1972 to 1974 he took the compulsory military service. He has lived in Prague since the late 1970s and was a part of the underground community around the Betlehem Chapel pub. He worked as an electrician, driver’s assistant, janitor, nurse and boiler operator. In 1979 he attempted to emigrate to Sweden, where he travelled legally, but after an adventure, trying to get to the Netherlands with his friend, he was forced to return to Czechoslovakia. He experienced an existential crisis on his return and took a serious interest in India, yoga and buddhism. He took Sanskrit lessons from Dušan Zbavitel and, from 1984, attended private flat seminars led by Milan Balabán, Egon Bondy and Milan Machovec. After the revolution in 1989 he passed his “maturita” exam and started studying Sanskrit at Faculty of Arts, Charles University, of which he graduated in 1995. He then went on to a postgraduate study of systematic philosophy, which he finished in 2002. He has been with the Oriental Institute of the Academy of Sciences since 1997, in 2002 to 2015 he worked as a teacher at the Institute of Philosophy and Religion, Faculty of Arts, Charles University. He is married with three children.