We can forgive, but we must never forget

Stáhnout obrázek

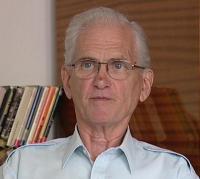

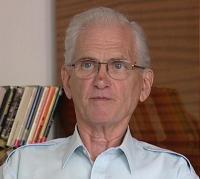

Fridrich Fritz was born on March 4, 1928, in the town of Prešov. He spent his childhood and youth in Prešov and in Bardejov. In 1944 when German troops were in retreat, he was abducted to the forced labour camps in Germany, though he was just sixteen. He went back to the village of Granč Petrovce because their flat in Prešov was strafed. His family had to find a new house in Levoča where he finished grammar school and passed school-leaving examination. Then he decided to study theology. When he was in seminary, he witnessed abduction of nuns, secret ordaining of bishop Barnáš, occupation of seminary by the State Security, and finally its dissolving in 1950. He got a draft notice, but he ignored it. In summer he secretly delivered counterfeit identity cards to priests who were detained in Podolínec. In autumn on September 26, 1950, in Bohemian Forest he tried to illegally flee across the border with an intension to continue studying theology abroad. While the train was in the border area, however, he was detained by the border guard. Investigation followed, then imprisonment in Český Krumlov from where he was transported to České Budějovice and later to Levice. He should have been convicted there. At that time the State Security revealed the group that was responsible for making counterfeit identity cards and people smuggling. It influenced all the follow-up events. Fridrich Fritz was transported to Prešov, where he was investigated. It took five long months, which he considered to be the most difficult time period of his life. He was involved into „Martin Hritz and co.“ process. On July 4, 1951, together with another thirteen accused men, he was put on trial. He was found guilty of the offence of high treason and sentenced to twenty years of imprisonment, got a penalty of 30.000 Czechoslovak crowns, his entire property was confiscated, and he was also deprived of his civil rights for ten years. Imprisonment followed. Firstly he was in Leopoldov prison, then in Ilava and finally in Mírov. Thanks to the hard work and influence of many precious men, he regarded his imprisonment as an important life lesson. He spent nine years, nine months and thirteen days in custody. In 1960 he was released by the general amnesty of Antonín Novotný, President of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (ČSSR). After coming back from prison he had to demand recognition of his rights from the President. His life destiny influenced also lives of his daughters who despite their excellent academic achievements couldn‘t have studied at universities.