Dust, ash, dogs, and orders - that was Auschwitz

Stáhnout obrázek

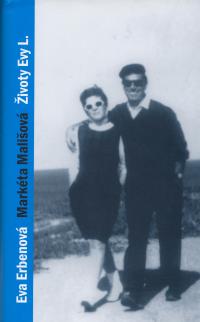

Eva Erbenová was born October 24, 1930 in Děčín as Eva Löwidtová. She comes from a wealthy assimilated Jewish family. Her father Jindřich Löwidt worked as a chemist and her mother Marta was a housewife. In 1936 the family moved to the Prague-Strašnice neighbourhood. Her parents tried to dispatch Eva to Great Britain before the outbreak of WWII, but she refused. On December 10, 1941, the Löwidt family was deported to the ghetto in Terezín. Eva lived with her mother and later also with her father in a remodeled attic and she did agricultural work together with other children. Her father was deported to Auschwitz at the end of September 1944, and Eva and her mother followed him there on October 4, 1944. At the beginning of January 1945 she and her mother were evacuated from Auschwitz to the camp Gross Rosen. Nazis evacuated the camp again in April as the war front was approaching, and the prisoners set out on a death march. Eva‘s mother died on April 17, 1945 near the concentration camp Svatava in the Karlovy Vary region. After her mother‘s death Eva fled from the death march and several days later she got to the village Postřekov where the family of Mr. and Mrs. Jahn took care of her and provided her with a hiding place until the end of the war. Eva‘s aunt from Heřmanův Městec found Eva after the liberation, and Eva then lived with her for one year and afterwards she went to Prague to the Jewish orphanage in Belgická Street. She took a course for nurses and later she befriended Petr Erben. She went with him to Paris in August 1948, and from there the couple continued to Israel. Mr. and Mrs. Erben had three children in Israel. Eva Erbenová wrote autobiographical books titled „Mom, Tell Me How It Was“ (1994) and „Dream“ (2001). Her fate is also depicted in the book by M. Mališová titled „The Life of Eva L.“ (2013). Eva Erbenová and her husband live in Ashkelon.