Do you really want to come back?

Stáhnout obrázek

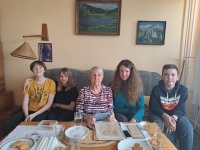

Olga Dvořáková, née Princová, was born on 27 July 1944 in Třešt‘, where she spent her entire childhood with her family. Her father, Karel Princ, was active in the anti-Nazi resistance, was imprisoned by the Nazis, and was saved from execution at Nuremberg by a typhus infection, which he survived and lived to see the Americans liberate him. Olga Dvořáková‘s grandparents owned a bakery and shop, which was confiscated by the Communists in the 1950s and they had to work in a large bakery. They then lost their savings due to currency reform in 1953 and spent the rest of their lives in poverty and substandard conditions. Because of Karl Prince‘s anti-fascist activities during the war, the family came under the scrutiny of the communist regime. After the revolution in Hungary in 1956, the family was monitored, as was the mail and parcels they received. Olga Dvořák was prevented from attending secondary school because of her unsatisfactory backgound reference. Eventually, she was admitted to the secondary medical school in Brno at the second attempt, thanks to her father‘s acquaintance and under a different name. Since her parents did not want to repeat a similar situation with their younger daughter, Olga‘s sister, they decided to sell their house in Třešt‘ and moved to Brno. Olga Dvořáková was about to leave for a study stay in Switzerland on 22 August 1968, when on 21 August the Warsaw Pact troops invaded Czechoslovakia. At the insistence of her parents, the witness went to Switzerland anyway, but returned to her homeland two months later, despite her parents‘ wishes that she remain abroad. In 2023, Olga Dvořáková was living with her husband in Brno.