I can‘t die, I have to wait for Pepík to come back from prison

Stáhnout obrázek

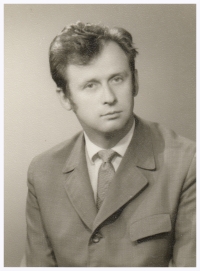

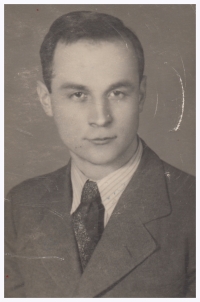

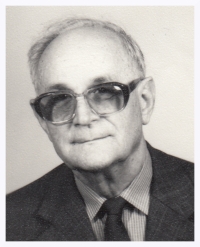

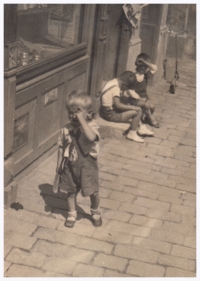

Josef Diviš was born on September 2, 1939 in Pardubice. He spent his childhood in Skuteč, where his father ran a successful bookbindery and bookstore. Josef Diviš senior, a successful businessman, an active member of Sokol and the Czechoslovak National Socialist Party, faced a number of provocations by the regime after 1948 with his family. In 1958, he was unjustly sentenced to five years in prison. He served his sentence in, among other places, the Rovnost camp in Jáchymov area. Josef Diviš and his brother Petr were expelled from the university and their sister Vilemína was fired from her job. After completing basic military service and several demanding professions in a stone pit or in construction, Josef Diviš got a job at a distillery in Pardubice, where he also received a recommendation to study. Before long, he moved to a maintenance job at a distillery in Chrudim. In 1972, he successfully completed his studies at the University of Chemistry and Technology in Pardubice, and ten years later he also completed postgraduate studies at the University of Chemistry and Technology in Prague. After 1989, as a director, he put the Chrudim distillery through the tough tests of economic transformation and was also behind the so-called Bioethanol project. He also worked as an opponent of final student theses, a reviewer of professional magazines or as a designer. He and his wife Iva raised daughters Iva and Jana. In 2023 he lived in Chrudim.