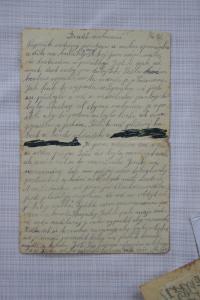

We were patriots, we fought. We just didn‘t wait to see what was going to happen

Stáhnout obrázek

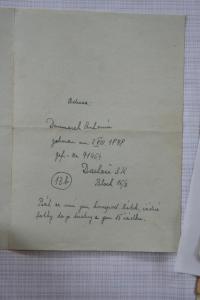

Alois Denemarek was born in Dolní Vilémovice in the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands on June 21st, 1917. He grew up together with four siblings in a farming family. He joined the Army in 1937. He got to the dragoons in Pardubice after being in Jihlava and Hradec Králové. His commander was the parachutist-to-be Alfréd Bartoš. His compatriot and friend Jan Kubiš, whom he kept in touch with during and afte the war, persuaded him to emigrate after the occupation. Later on he kept in touch with Kubiš around the assassination. The Denemarek family hid parachutist Pospíšil in their house. Both the parents and the brother of Alois Denemarek were arrested after the betrayal and they died in concentration camps. Alois Denemarek escaped his fate - shortly before that he got married and moved with his wife to another village. They confiscated his farm after the war and the arrival of Communism. He was arrested and worked in the glassworks. He worked in the PTP (Auxiliary Technical Troops) for 18 months. Then he worked in the vineyard in Znojmo.