I‘ve never been anywhere. But I wanted my son to be able to study

Stáhnout obrázek

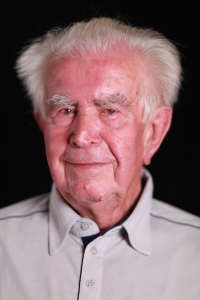

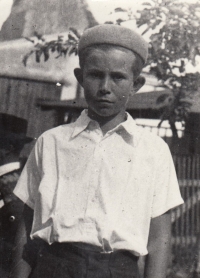

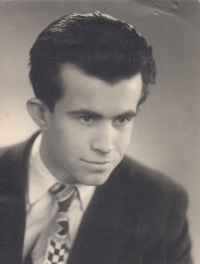

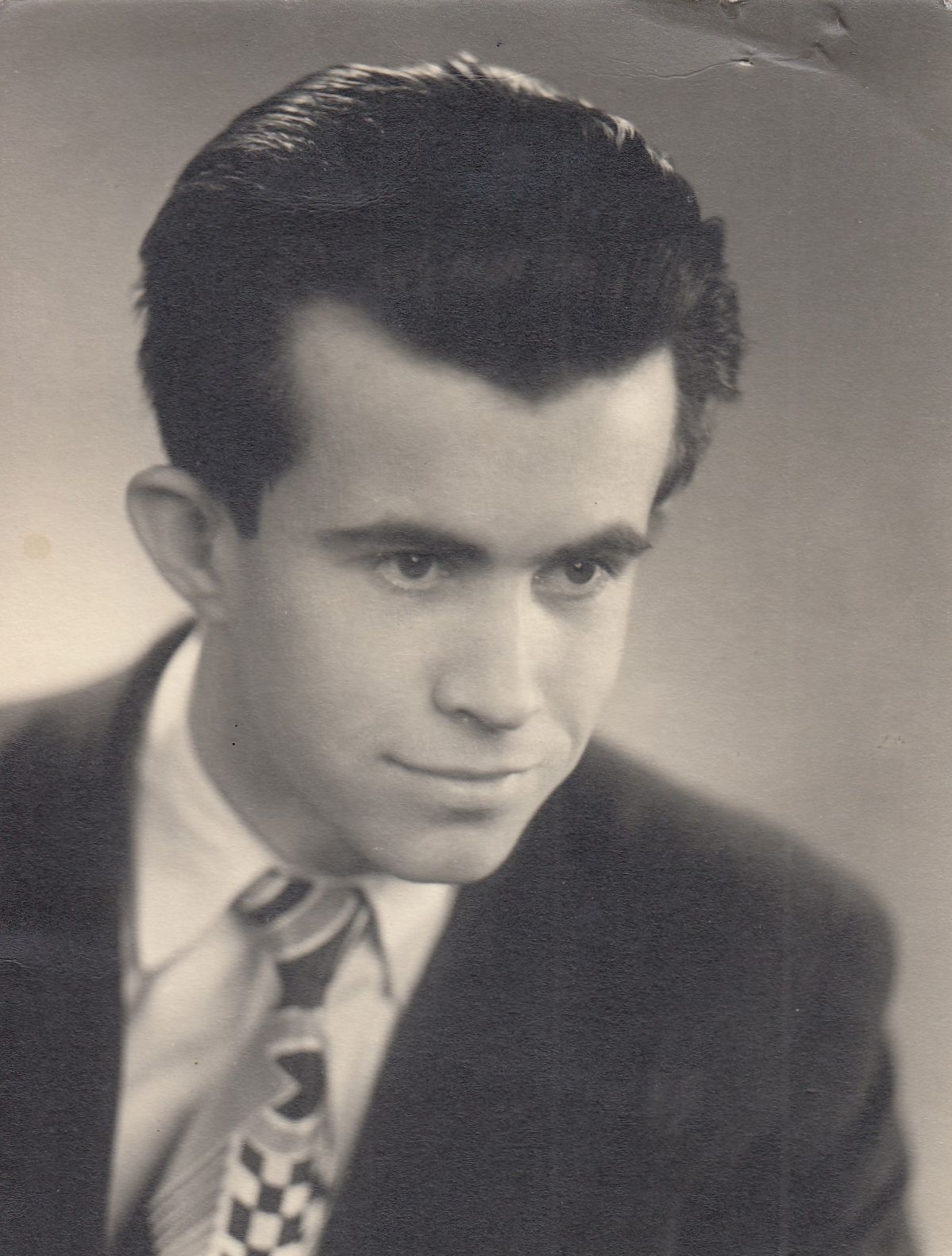

Jiří Cimrman was born on 30 October 1935 in Benešov to Jarmila Cimrman, née Rybková, and Václav Cimrman. The family moved frequently because of his father, an employee of the Czechoslovak State Forests and Estates. When they lived in Mariánovice, Jiří became friends with two boys from the concentration camp in nearby Bystřice u Benešova. Towards the end of the war, they hid in their home. The first black man he saw in his life was a dredger, an American fighter pilot who flew over the farm in Mariánovice. When they moved to the farm in Krukanice, they were given a ride by liberating American soldiers. In 1950, Jiří Cimrman joined the Czechoslovak Construction Plants in Pilsen as a bricklayer‘s apprentice. In 1955, he graduated from the Higher Industrial School of Construction and joined the national gravel mining company in Prague as a builder. In the same year he joined the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, where he remained until 1989 despite his opposition to politics. He agreed to the occupation of Czechoslovakia on 21 August 1968 so that his son Pavel could study. In 1969, his sister Libuše Cimrmanová emigrated to America, which, according to him, had a major impact on his mother‘s health. He later worked as a gravel inspector at the West Bohemian stone industry. In 1959-1977 he was employed in the design centre of the Stavopodnik construction cooperative. Until 1990 he worked as a builder in the design department of the state enterprise Road, based in Pilsen-Litice. At that time he was elected to the company party committee, later becoming its chairman. Until his retirement in 1995, he worked as a builder in the Czech Insurance Company. At the time of filming (2023) he lived with his wife Růžena, née Soukupová, in Plzeň-Křimice. Their son Pavel unfortunately succumbed to a serious illness at the age of fifty-six.