Girls were walking outside and chestnut trees were starting to bloom. And I was in prison

Stáhnout obrázek

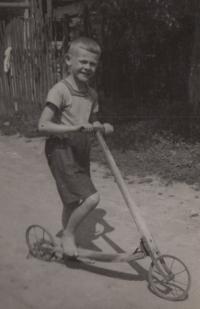

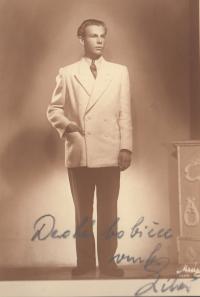

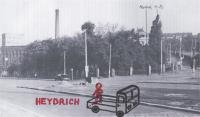

Liboš Buben was born on May 9, 1926 in Rychnov nad Kněžnou. In October 1941 he and his mother moved to Kobylisy in Prague. When he was sixteen years old, he witnessed first-hand the site of the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich shortly after the attack. In autumn 1944 he began working in the General Headquarters of the Škoda company in Prague as a technician for typewriters and computing machines. On February 14, 1945 he watched the American bombing of Prague from the roof of the company‘s building. The next day he was sent to Brno to work on digging trenches there. Two months later he became sick with scurvy and he nearly succumbed to the disease. On May 5, 1945 he was on Wenceslas Square when the Prague Uprising broke out. Liboš found a shelter in his workplace. He was issued a rifle and until May 9 he monitored the situation from the roof of the building (present-day City Hall of Prague and Palace Adria). In autumn 1948 he began his basic military service in the Military Hospital in Prague-Střešovice. Half a year before his duty was over he was accused of allegedly defaming the army and the officers‘ corps and without a chance for defending himself he was immediately put to the army prison in Prague-Hradčany. He was sentenced to seven months in a labour camp. Liboš served his sentence in a quarry in Dobřichovice and in the stronghold in Kuřivody where he was doing reconstruction work. When he completed his sentence he had to serve additional seven months in the Auxiliary Technical Battalions. He returned home in spring 1951 and he began working as a repairman of boiler systems in the company Sdružená řemesla („United Trades“) and later he worked in the same company as a repairman of elevators. At the end of the 1950s he worked as a serviceman of forklifts and then he worked on elevators again. He retired in 1986. Died in March 2017.