To keep an optimistic outlook on life is the best guarantee for happiness in life

Stáhnout obrázek

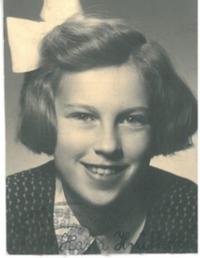

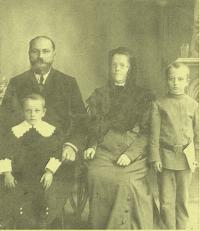

Hana Blagodárná (neé Hnitková) was born on 3rd March in Prague. Her father came from a family of teachers in Kralupy and her mother of a farmer´s family in the Roudnice area. She has been living in Prague 6 all her life. After the 1948 February coup her father was taken into custody for being active in not accepting the land confiscation. After his release, he was banned to teach in Prague and later forbidden to appear behind the teacher´s desk at all. He worked at the Kladno ironworks until his arrest by the Police and sentenced in a show trial to 11 years in prison. He was released after over two years thanks to the amnesty. Her mother and two children were thrown out of their flat and the whole six-member-family had to share a one-room-flat. Despite all this, Hana was accepted to study at the Pedagogical Gymnasium, became a teacher of primary school children and later married a son of a Russian emigrant.