Only stones remained from our family home, but we uncovered the church foundations after the fall of the Iron Curtain

Stáhnout obrázek

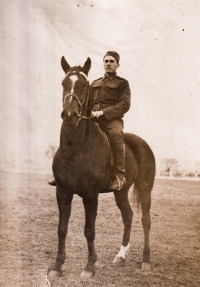

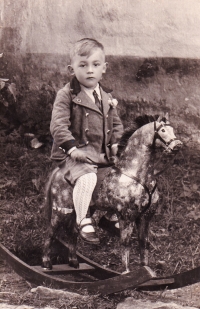

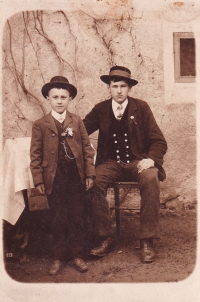

Emil Baierl was born on 8 December 1933 in Uhliště in Klatovsko Region (Kohlheim in German) and grew up in a large farmhouse with a cobbler’s workshop in nearby Fleky (Flecken). People spoke exclusively in German in Fleky, just like in the now-defunct village of Červené Dřevo (Rothenbaum), where Emil went to school and which used to be the site of the pilgrimage church of Our Lady of Sorrows. Here Emil occasionally served as an altar boy during mass, it was also the only church for the inhabitants of several nearby Bavarian villages. Emil’s father served in the Czechoslovak Army, but prior to mobilisation in 1938 he fled over the border into Bavaria, and as a deserter he was prohibited from returning to Czechoslovakia after the war. In 1939 he enlisted in the German Army and fell into captivity. After the end of the Second World War, Emil and his mother began systematically smuggling things to the Bavarian side of the border – out of fear of deportation. Each night they squeezed their most essential belongings into sacks and carried them across the border until the arrival of the Czechoslovak Army in November 1945. In March of 1946, he and his mother and younger brother crossed over one final time. They lived in temporary quarters in a cowshed until moving to Neukirchen in 1948, where Emil received training as a cobbler. Emil watched the building of the Iron Curtain and destruction of the border villages from Germany, only returning to Bohemia after the borders opened in 1989. His first journey was to their house in Fleky, where only a pile of stones remained. On the location of the destroyed village of Červené Dřevo, Emil and other locals managed to discover the site of the original church. They gradually uncovered the entire foundations, built up some peripheral walls, renovated the tombstones at the erstwhile cemetery and had a commemorative plaque installed.