It is my life‘s debt to pay tribute to my uncle who was assassinated in Mauthausen in April 1945

Stáhnout obrázek

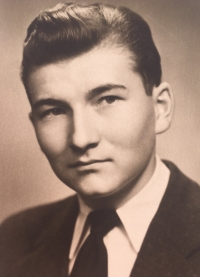

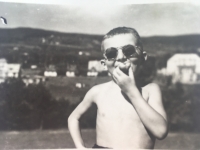

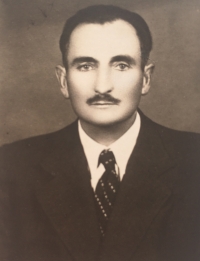

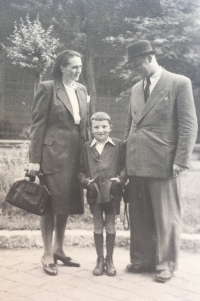

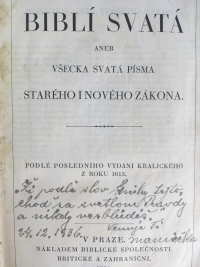

Ľudovít Sabadoš was born on June 19, 1937 in Gán and from the age of three he grew up in Bratislava with his uncle and aunt, who are still a father and mother for him. Uncle Valér Kubáni was an officer in the Czechoslovak Army and after the establishment of the Slovak Republic he served in the Slovak Army. He and his wife were involved in the resistance - little Ľudovít accompanied his aunt in smaller activities, such as helping defectors from the Slovak Army, who wanted to join the partisans. Valér Kubáni was arrested on February 5, 1945, and Ľudovít subsequently witnessed an hours-long home search of the apartment by the Gestapo. Uncle was imprisoned in the Palace of Justice; Ľudovít also witnessed the loading of prisoners into trucks in front of family members and their transport to the Bratislava main station. On March 31, 1945, Ľudovít‘s uncle Valér Kubáni was deported from Bratislava together with another 100 political prisoners to the Mauthausen concentration camp and immediately upon his arrival, on April 10, 1945, he was murdered in a gas chamber. After the war, Ludovit remained with his aunt, although his parents still lived in Gana. In 1948, efforts to obtain information about the fate of the transport were interrupted, as there were no witnesses or written records from Mauthausen. After liberation, Ľudovít engaged in scouting, but in 1949, StB invaded the summer camp, disbanded it and the children were immediately taken home. After returning to Bratislava, the ŠtB interrogated the children as well. Ľudovít graduated a chemical high school. He lived with his aunt until her aunt‘s death, and later Ľudovít‘s parents moved in with them. He was successful in several workplaces, especially in research. Thanks to his work in the Camping and Caravanning Club, where he held the position of chairman, he traveled to the West several times and visited the Mauthausen Memorial a few times on the way home. Since the circumstances of the last transport from Bratislava are still not sufficiently researched and the society has in no way shown respect for the murdered, he has been engaged in its own research for five years, with which he wants to pay tribute to his uncle‘s memory.