S naší rodinnou historií jsem se seznámil až v Izraeli

Stáhnout obrázek

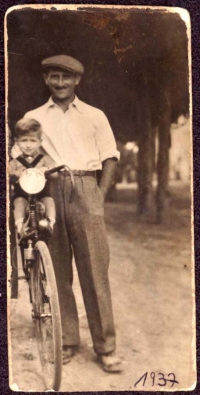

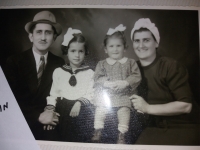

Pavel Friedmann se narodil 25. března 1948 v Michalovcích na východním Slovensku v židovské rodině, dětství prožil v obci Malčice. Jeho rodiče, otec Izák a matka Dora, přežili holocaust - otec v koncentračním táboře Dachau, matka se skrývala s falešnými dokumenty v Maďarsku. Otec pracoval jako lékárník v Malčicích, matka mu vypomáhala. Pavel Friedmann po ukončení základní školy v Malčicích pokračoval ve studiu na střední průmyslové škole v Košicích. V roce 1964 se rodina Friedmannových rozhodla vystěhovat do Izraele, kde žili od předválečné doby čtyři matčini sourozenci. V Izraeli pamětník nastoupil v letech 1967-1970 tříletou vojenskou službu, poté odmaturoval a v roce 1975 ukončil studium na elektrotechnické fakultě. V dalším studiu později pokračoval v letech 1981-1983 na univerzitě v Buffalu ve státě New York. Od roku 1985 pracuje pro izraelskou elektrárnu. V letech 1994-1995 působil jako zástupce Židovské agentury v Praze. S manželkou Relly vychoval syna a dceru. Pavel Friedmann žije v Haifě.