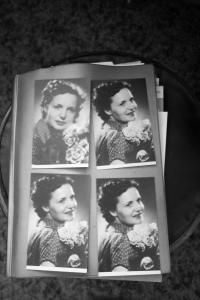

Milada Všetičková

* 1916 †︎ 2008

-

“I was born January 28th 1916, in a family that was not particularly wealthy. There were our parents and us, three daughters. My father was a railways official. Later he became a secretary for the railways employees and then he was elected to the National Assembly in 1929, and he served there till 1935. And his electoral district was as far as Carpathian Ruthenia, he travelled there often. And he was full of compassion with those people, for he had seen the poverty they lived in. So he would always leave home, equipped with lot of clothing, whatever he could carry, and then he would return hardly dressed at all, because he had given it all to the people there. My mother stayed at home, and she must have been a very good housewife, it was surprising that she manage to save for a dowry for all three of us daughters when we got married.”

-

“We arrived there early in the morning, submitted our permits, and now imagine that: one by one the others were called in, and we were not called, nobody called our names. At two o’clock in the afternoon they said: ´The visiting hours are over.´ We said this could not be, that we had been waiting from the early morning, and we needed to see him, so we were eventually granted permission. My father spoke German fluently, so he objected this way. So they led us directly into the jail. The other prisoners who had visitors were always brought to the office outside of the jail, but we were taken directly into the prison. And everything was already prepared beforehand. A big room, a small table in the corner and my husband was sitting behind that table. Seven or eight Gestapo members were standing behind him. So there was the distance between us, the table stood in our way. And again, only family matters, no other talking is allowed. We brought lots of food with us, the best we could obtain; we wanted to give him something. But they did not allow anything, anything at all, not a single bit. And I had my muff placed on the table, and in it I had a small packet of cigarettes. So I tried to slide it across the table, to pass him the cigarettes at least. It was dreadful to watch, because I saw that he was at a loss, he did not know how to take it, and where to conceal the cigarettes, so that the Gestapo men would not notice, and so he said: ´At least I will get a piece of bread for it.´ This was terrible, terrible. For you cannot even imagine, when you bring so much food, and he, a smoker, exchanges the cigarettes for a little piece of bread! So we managed to get permission to send him bread regularly. In the Highlands, there was a baker making bread for him, and sending it to the prison. So we hoped he was receiving at least some of it. But that was our last meeting; we never got to visit him again.”

-

“But now to tell you how we first met. This was in the Orlí Street, where we had a two-room flat. My sisters were no longer living with us, they were already married. And one day I was leaving for school, and in the entrance hall I met a soldier. I did not know who he was and I had no clue about the army ranks and such, but I simply liked him. He seemed all in shining gold, you know, his appearance; you can imagine how exciting it must have been for an eighteen year old girl like me. And when I came back from school that day, I learnt that a new tenant has moved to our neighbor’s flat. And this tenant was general Všetička. So I would often meet him on the stairs, he would greet my Mom, because the neighbour had introduced him to her, but would not greet me, a silly teenage girl. I always just looked at him, but I have to say there was some interest on his part as well, for he would return my looks. However, after six months it was over; the nice officer was no longer living there. And I learnt he was provided with a room in a dorm, and he moved to Alfa. So the contact between us was now interrupted. But chance does play an important role in our lives. One day I went by train to Česká Třebová where my ´aunt´ lived; she was my mother’s friend, and I would sometimes go visit them. They had no children of their own, so they were always happy when I visited them. They were very nice. So I was on my way to my aunt, and I met him again. I recognized him immediately, of course. We kept looking at each other, and then he eventually summoned courage and asked me: ´So you happen to be the daughter of Mr. Deputy Malý?´ ´That’s right.´ And we chatted all the way to Česká Třebová. He politely helped me with my suitcase, he was a gentleman, very courteous, and I – beaming with joy – went to my aunt’s place.”

-

“These two officers were very polite. One of them had worked as an editor before, I don’t know what the other’s profession was, but they were both extremely courteous. For instance, they showed us on the map where they were stationed, and where their armies were. And when we asked why they (their soldiers) behaved that way, like raping young girls and so on, he says: ´You know, those soldiers are former prisoners, and we simply have no control over them, we are not able to hold them back.”

-

“I was to meet my former classmates in Café Slavia. And my husband tells me: ´I will pick you up afterward, and we will go home together.´ So I spent some time with my friends and when my husband came, he just said: ´I will only have one coffee, and then we go.´ Meanwhile the waiter came: ´General, there are some gentlemen waiting for you by the cloakroom.´ So my husband got up and went there, and the girls then told me: ´Your face was just as pale as this tablecloth.´ And my husband comes back and says: ´Look, we pay the bill and leave. The Gestapo came for me.´”

-

“I was at home with my parents and all of a sudden… I got up in the morning and went to the kitchen and said: ´Somehow, I don’t have any appetite for my breakfast today.´ And my father only told me: ´No wonder.´ And this was enough for me and I asked: ´What happened to Mítěnka?´ And he said: ´Karel, your brother-in-law was here yesterday, and told us there are already posters in the streets informing of his death.´ And this is the way it was, that’s how I learnt about it. Later, I received the Sterbeurkunde, or notification of death. It was difficult, very difficult…”

-

“One day, we had just eaten our lunch and I was sitting in the garden and putting my baby to sleep, and my parents call me to come. Suddenly I see my husband with the Gestapo. And I just thought – what is going to happen? What do they want? And he told me he only came to pick up some keys. But it was only a pretext. I suspect that the officer who investigated him allowed my husband to visit home. I have this feeling, because they did not take anything, we did not have anything, anyway. And I only asked them if I could give my husband something to eat, that we have just had our lunch, we had tomato sauce that day, I will never forget that as long as I am alive. So they allowed him to eat it, and then they took him away.”

-

Celé nahrávky

-

Brno, 28.01.2007

(audio)

délka: 01:35:31

Celé nahrávky jsou k dispozici pouze pro přihlášené uživatele.

Look, we paid the bill and left. Then the Gestapo came for me.

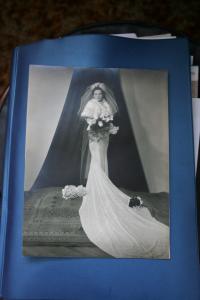

Milada Všetičková was born January 28th 1916 in Brno. She was the second wife of general Bohuslav Všetička, who was executed during the occupation for his activities in the resistance group Obrana Národa (Defence of the Nation). In her narration, she tells of the dramatic events during the Protectorate, and of her brief but happy marriage before the general‘s arrest. She graduated from the Masaryk‘s State Institute for training of vocational schools teachers, in 1938 she married Bohuslav Všetička. They lived shortly in Trenčín, after the collapse of the post-Munich Czechoslovakia they returned to Brno. After his arrest (February 29th, 1940) and execution (August 8th, 1942), she cared for her family; unfortunately both their children tragically died. She was active in the Czechoslovak Association of Legionaries; notable also are her lecturing activities for students. She died April 18th 2008 in Brno.