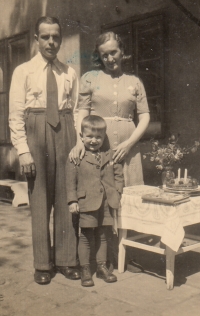

What‘s gonna happen to the boy if I get shot?

Stáhnout obrázek

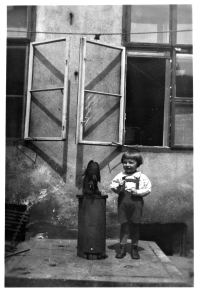

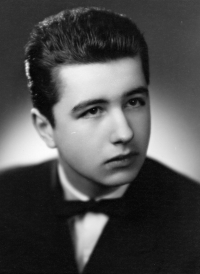

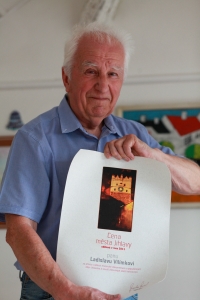

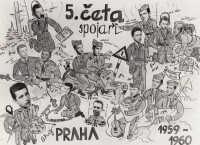

Ladislav Vilímek was born in Brtnice on 29 May 1940 to Ladislav and Ludmila Vilímeks. His father was deployed in a missile factory in 1939. His brother Jiří was born in 1944. During the liberation he once ran away from a plane firing a machine gun and a soldier firing a submachine gun. He saw a charred human body in a destroyed tank near the cemetery. After the war, he used to walk past a camp for displaced Germans in Staré Hory. His father got back to producing electric motors after the war and ran the business until the Communists nationalized it in 1948. From age six, he was an altar boy at the Minorite church where he met the sculptor Jaroslav Šlezinger who ended up in uranium mines. In the 1950s, he exchanged letters with a friend from West Germany, and his father was interrogated by the StB. At 14 he wanted to become a priest, but ended up at a mechanical engineering high school. He painted and played the theatre. He took his military service with a special anti-nuclear defence unit in Prague. He then worked in Jihlavan and Oseva. A few days after the Soviet invasion in 1968, his son died in the maternity ward. He wrote several books about the houses and Jews of Jihlava and received many awards for his contributions in the field of history. At the time of filming in 2023, he was living and working in Jihlava.