I would never return to communist Czechoslovakia

Stáhnout obrázek

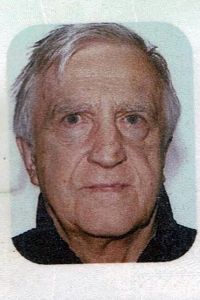

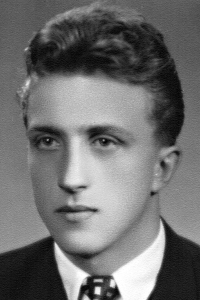

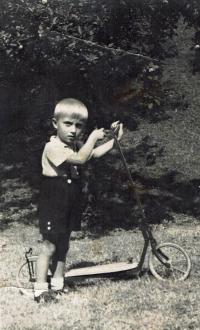

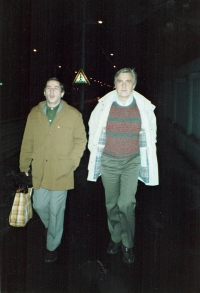

Josef Tomáš was born on 23 November 1933 in the family of a postal clerk in Polička. He grew up in Česká Třebová, where he lived through the German occupation from 1939 to 1945. After the war he moved with his parents to Chocen. He graduated from the grammar school in nearby Vysoké Mýto. His close friend from the Scouts, Jiří Mráz, was one of the victims of the political trials in the 1950s. In the monster trial of Stříteský and Co. he was sentenced to sixteen years for alleged treason. Josef Tomáš graduated from the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering at the Technical University in Prague. After his studies, he lived in Liberec. He taught at the industrial school there and worked as an assistant at the university. He married and had two children. From 1962 he worked as a scientist at the Slovak Academy of Sciences in Bratislava. In 1968 he went to West Germany on a scholarship and never returned to socialist Czechoslovakia. His family emigrated with him. From 1971 to 1976 he worked at the Volkswagen research centre in Wolfsburg. In 1976 he moved to Melbourne, Australia, where he taught at a technical university. In Australia he began writing poems and publishing collections of poetry. He also worked on translations of Czech poets into English. In 2021 he was living in Melbourne.