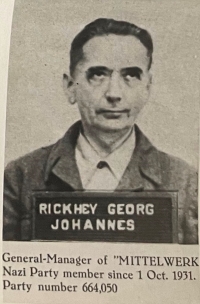

The brother-in-law was persecuted by both totalitarian regimes, he did not even live to see the restitution

Stáhnout obrázek

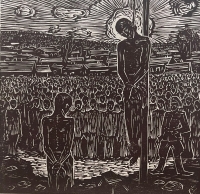

Jiří Suchý was born on 18 May 1944 in Mirošov. From his parents he absorbed information about the course of the war in Podbrdsko and the liberation on the demarcation line. He recalled, for example, the dramatic event when the retreating German army wanted to blow up Mirošov. There was also a Nazi disciplinary camp in Mirošov during the occupation, and after the war, according to the witness, it was a home for Germans unable to be removed. From the story of his older sister Emilia Urbanová, the witness learned about the massacre of German soldiers at the Mirošov castle. Jiří Suchý trained in two trades and completed his secondary education, then spent his entire working life in the metalworks in Rokytnice, where he was also on the night shift on 21 August 1968. Shortly after the occupation by Warsaw Pact troops, he married and started a family. As a young man, he was struck by the story of his brother-in-law Karel Urban, who joined the anti-Nazi resistance and was imprisoned in several concentration camps. After 1989, he tried to help his nephew with the running of the farm returned in restitution. At the time of filming in 2023, Jiří Suchý was retired and tending to the house and garden.