Masaryk‘s „not to be afraid and not to steal“, to be considerate of others and behave in such a way that one can look back on one‘s actions without blushing

Stáhnout obrázek

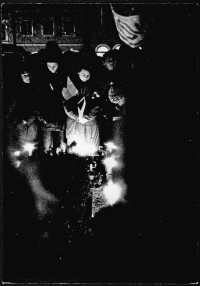

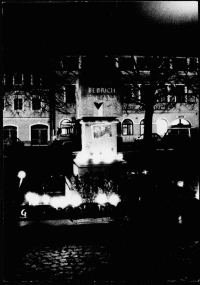

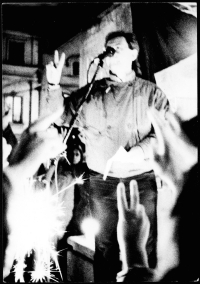

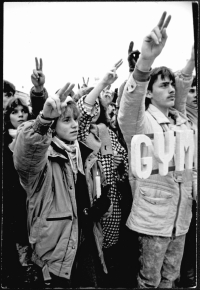

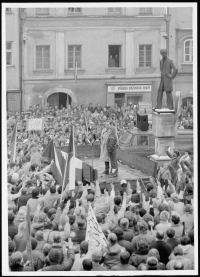

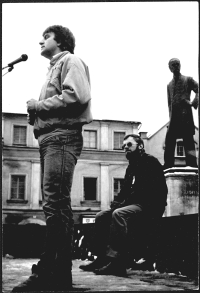

Vojtěch Stříteský was born on September 30, 1961 in Litomyšl and comes from a family with nine children. They went to church, as was common in the Litomyšl region, and he was a minister from the age of five. Religion was later the reason why his sister could not study at a teacher training school and his brother was labeled a religious fanatic by the regime. He experienced the occupation in 1968 in his hometown, watching the arrival of tanks and armored cars with his whole family from the scaffolding on the house. He began to attend the high school graduation course waiter, but in 1979 he joined the newly opened conservatory in Pardubice, where he studied opera singing for six years. In 1982, he and his friend founded a successful Film Club, which showed a film every two weeks with an introduction by a lecturer. In 1989, he was an eyewitness in Prague and experienced the atmosphere there during the anti-regime protests. After returning home, together with others, he began to organize meetings at the monument of Bedřich Smetana. Seven people also founded the local Civic Forum. After the Velvet Revolution, he participated in municipal politics as a representative, councilor and deputy mayor. Since 1983, he has been involved in the founding of the Smetanova Litomyšl festival, and since 1992 he has been its artistic director and dramaturg. He likes music, movies and traveling.