All my life, I‘ve heard the roar of planes

Stáhnout obrázek

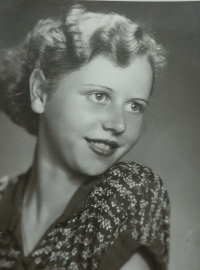

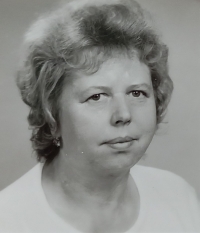

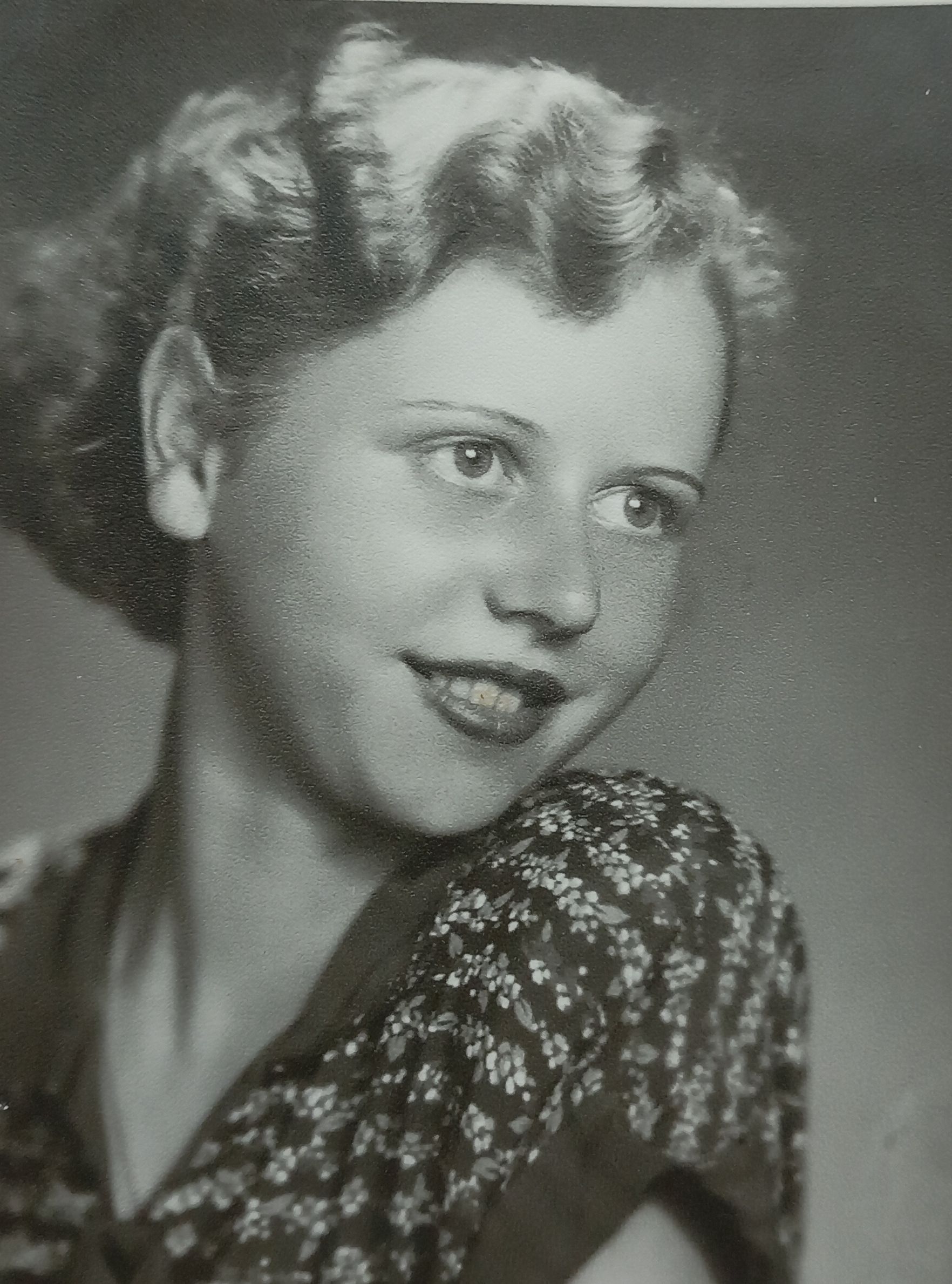

Marie Šimánková, née Steffl, was born on 24 May 1936 in the village of Malčice as the only child of her Czech mother Kateřina Steffl, née Zikešová, and her German father František Steffl. Her Czech-German family was faced with expressions of hatred towards the Czechs before the war and towards the Germans after the war. In 1942, her father had to join the German army. He fought on the Eastern Front, where he was captured towards the end of the war. He did not get home to Czechoslovakia until 1946. The family had no news of him for four years. The Steffl family spoke only German. Marie Šimánková learned Czech only after the war in a Czech school. During 1944, she experienced many air raids and bombings in the vicinity of Malčice and Přídolí. At the end of the war, she met both the Soviet and the American armies. All her father‘s siblings were deported to Germany after 1946 based on the Beneš Decrees. The Steffles were allowed to stay. Before the removal, the relatives were held for some time in a makeshift internment camp in Vyšný near Český Krumlov, where they gathered deported Germans waiting to be taken to Germany. Marie Šimánková and her parents visited the relatives in Vyšný several times. From the 1960s onwards, they could see their relatives in Germany, and the relatives could go to Czechoslovakia. After training as a hairdresser in 1953, she worked in various positions. In 1957 she married Josef Šimánek, and together they had four children. At the time of filming (2023), she lived in Velešín.