They closed the shop, took the mother away and left us alone

Stáhnout obrázek

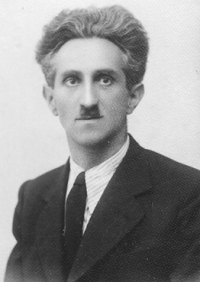

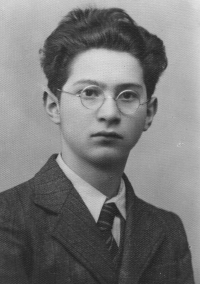

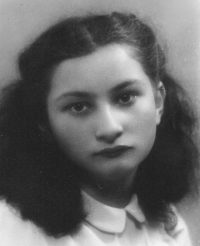

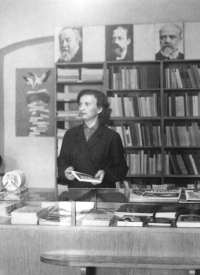

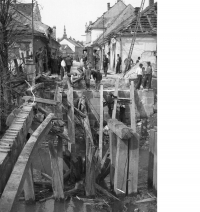

Lubomír Šik was born in Litovel on February 2, 1928 into a family with Christian-Jewish roots. Father Karel Schick and mother Anna, née Staňková, ran a sewing workshop and a textile and seamstress shop in Litovel. Although both of them left the faith and, following the example of President Masaryk, became members of the Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren, they were considered a mixed marriage at the time of the Protectorate. They were formally divorced and his father was hiding until his death in 1941. Lubomír attended elementary school in Litovel and devoted himself to playing the violin. He was admitted to the grammar school, but in 1942 he had to leave because of his mixed-race origin. He was trained as a locksmith. His mother continued to lead the workshop and shop, but was arrested in January 1944. She was warned by the police about the sale of textiles without tickets. Lubomir and two years younger sister Jitřenka remained alone until June 1945. His mother spent her time in Jauer bei Liegnitz in present-day Poland and survived the death march. After the war Lubomír entered the secondary technical school in Šumperk. Here he led a scout unit, founded a school voice band and became an editor of the scout magazine Pětka and school magazine Průmyslovák. After graduation, he was placed in a new turntable production plant in Litovel, where he spent his entire life working for a break - first in the production management department and then in the computer centre. In addition to his work, he devoted himself to organizing cultural evenings with slide shows, led a corporate photo club, played and directed plays for the Litovel amateur theatre association and also participated in the activities of the youth tourist section, which under his leadership became the official Junák section. At the time of normalization, due to his attitudes and activities in Junák was transferred to the department introducing computer technology and remained there until retirement. During the Velvet Revolution, he became involved in public affairs. He became a founding member of the Civic Forum and a town councillor and chronicler. He wrote his extensive memoirs and is the author of a number of publications on the history of the city and gramophone production.