“I wouldn’t have stayed there anyway – we were four kids, too many to be able to live on it.“

Stáhnout obrázek

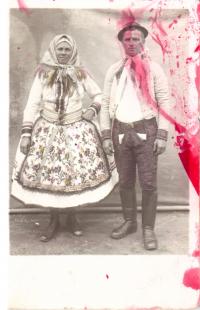

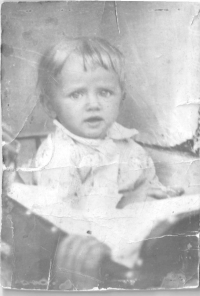

Terezie Sedlačíková, née Hubená, was born in 1932 in Nový Přerov in a Croatian family. She had two older brothers and a younger sister. Her parents were farmers. In 1938 she began to attend a German school, in 1945 a Czech one. Her father was drafted to the army and served in the war. He worked in the stables in Hodonín. He didn‘t return from the war anymore. By the end of the war she and her mother were hiding in a wine cellar. In 1948 they were expatriated to Dětřichov, where they were given an estate that used to belong to Germans. Terezie got a job in Moravolen in Hanušovice, where she worked for the rest of her life. Her husband was Czech and the language of communication with their children was Czech as well.