People should exercise even at ninety

Stáhnout obrázek

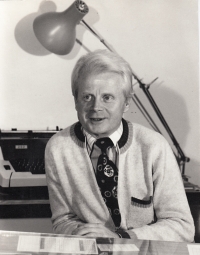

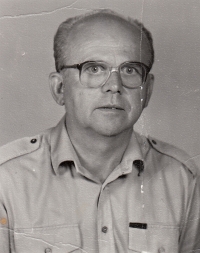

Josef Roubíček was born on 20 February 1934 in Mnichovice near Prague. His mother, Marie, née Vaňousová, a seamstress, came from Mnichovice. Her father, tailor Karel Roubíček, was born in Leipzig. They married in 1932 in Mnichovice. Josef grew up with his older brother Milan in a house on the square. From 1936 until the end of the war, the family lived in Prague. His mother ran a fashion salon, and his father worked in a photo shop. A younger sister, Jiřina, entered the family. By that time, Dad was already totally deployed in Hamburg. During the war, the parents helped people who were threatened with transport to concentration camps. After the war, they moved to Karlovy Vary. The father, a great sportsman and Sokol, also led his children to sports. In the 1950s, he was arrested for activities within the Sokol, and his older son was expelled from college. Karlovy Vary became Josef Roubíček‘s destiny. The sports-minded young man learned to ski and river raft here. In his spare time, he was active in sports. He competed in skiing and canoeing. After finishing his sporting career, he joined the Mountain Service at Boží Dar, where he worked for over 30 years. After 1989, he opened a sporting goods store. At 90, Josef Roubíček is still cross-country skiing and active in sports. In 2023, he lived in Karlovy Vary. The memoirs of the witness were filmed and processed thanks to the financial support of the Karlovy Vary Region.