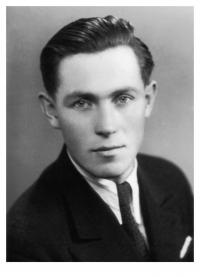

The 1938 certainly indicated a lot already

Stáhnout obrázek

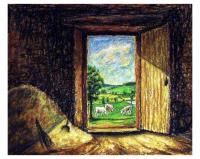

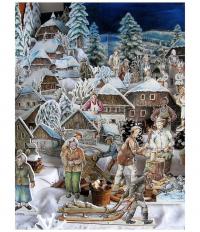

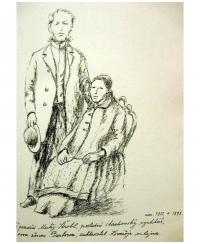

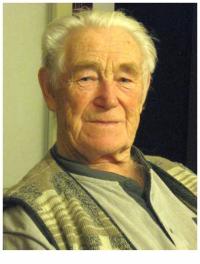

Jaromír Randák was born in a mill near Stachy in Šumava on May 8th, 1919. He was the second son of the local miller. He spent very tough but at the same time beautiful childhood there. He remembers local life during the First Republic, the coexistence of the Czechs and Germans, but also the occupation of the country by the Nazis in September 1938 and in March 1939. Just behind their mill there was the border line between the Sudetes at that time and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. So German soldiers often dropped in the mill. At that time Jaromír spent most time as a baker‘s apprentice in Písek. Later on he travelled the Republic for his job. He spent most of the War and its end in May 1945 in the family bakery in Slaný. It was where he experienced the night bombing of Dresden, which he initially thought was a storm. He witnessed shooting in streets, the arrival of the Red Army and the conditions within it, the flight and disarmament of the Germans and all the war suffering connected with it. He was conscripted into the army after the war. He spent most of his military service in a completely cleared-out village Litrbachy. It used to be a prosperous German little town in Slavkovský les, which was shortly after that blasted out of existence and razed to the ground during a military drill. Having finished his military service, Jaromír moved to Prague. He went through a few at that time already gradually nationalized bakeries. He also worked in the Kladno Steelworks. Within the terms of the campaign to boost industry, in the end he went involuntarily to Aero Vysočany, later ČKD traction, to machines and eventually to steelworks store. Apart from other people he met apprentice Karel Gott there or dodgem driver Vladimír Boudník whom he supplied with interesting sheet metals and with some other material. He worked in ČKD till he retired, he never came back to bakery again. He is still very active at his age, he enjoys being with children, grandchildren and he still goes in for his lifelong loves: playing the violin and especially drawing and painting. He is interested in the history of his native region and he is even an author of a unique Šumava crib with the land, buildings and figures from his native region.