It wasn‘t pretty at all in the war

Stáhnout obrázek

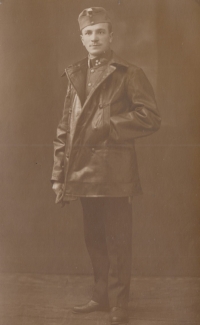

Valerie Princlová, née Vančoková, was born on March 10, 1932 in Pilsen. She had a carefree childhood until starting compulsory schooling on September 1, 1939, when World War II broke out. In 1944, the Nazis imprisoned her father Karel Vančok for illegal activities: He was then transported to the prison in the Small Fortress in Terezín. He was released from prison early the following year. Shortly afterwards, in April 1945, she witnessed the most destructive Allied air raid on Pilsen, when bombs completely destroyed the Škoda plant‘s corporate headquarters located opposite their home. Not long after, she welcomed the first American soldiers who came to liberate the city. She was a witness to a firefight between soldiers and a German sniper, which happened to be filmed by an American cameraman. Five years after the end of the war, she lost both parents. Nevertheless, in 1951, she completed a nursing school and became a midwife. As part of the currency reform, she was one of many who hastily spent her savings during the general shopping spree. Before that, she had already married and started a family. Her and her family got stuck in Yugoslavia in 1968, just as the Warsaw Pact troops were invading Czechoslovakia. They did not emigrate, they returned home. She later worked as a nurse until her retirement in 1992. In 2023, she still lived in Pilsen.