Somebody has to do it

Stáhnout obrázek

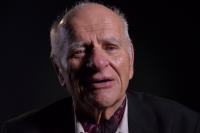

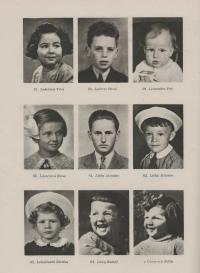

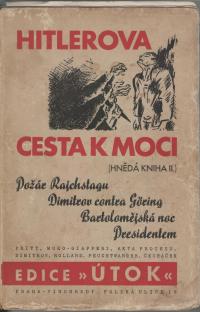

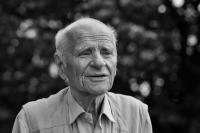

Igor Pleskot was born on 23rd November 1930 into the family of Jiří Pleskot, member of the Czech social democratic party. Both of Igor Pleskot‘s parents joined anti-nazi resistance (ÚVOD) immediately after the occupation of Czech lands. They were also active in the Sokol resistance and Masaryk‘s league against tuberculosis. Father of Igor Pleskot was providing ration stamps and IDs to the paratroopers from England. Igor Pleskot‘s parents were arrested after the assassination of Heydrich and execued in the concentration camp mauthausen on 24th November 1942. Igor Pleskot was transported along with his younger sister Milena to Jenerálka, and later on into the concentration camp in Svatobořice where they spent the rest of the war together with other children of the interned resistant fighters. After the war he started to study sociology and history and worked as a history teacher at the Faculty of Architecture of Czech Technical University in Prague. He was involved in the students‘ political movement in the 1960s. After the occupation of the Warsaw Pact army he was suspended from the university and had to accept a job in a building cooperative, then he made his living as an analytic and programmer. In November 1989 he was involved in Civic forum as a chairman of the strike commitee.