The years in the children´s home are such a blank space

Stáhnout obrázek

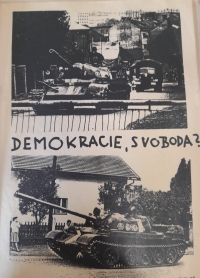

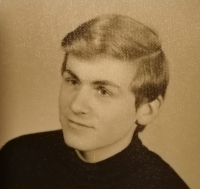

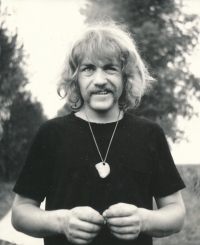

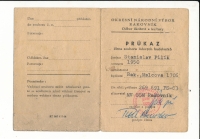

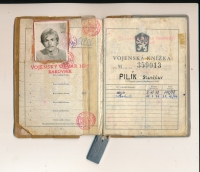

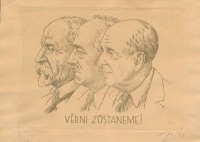

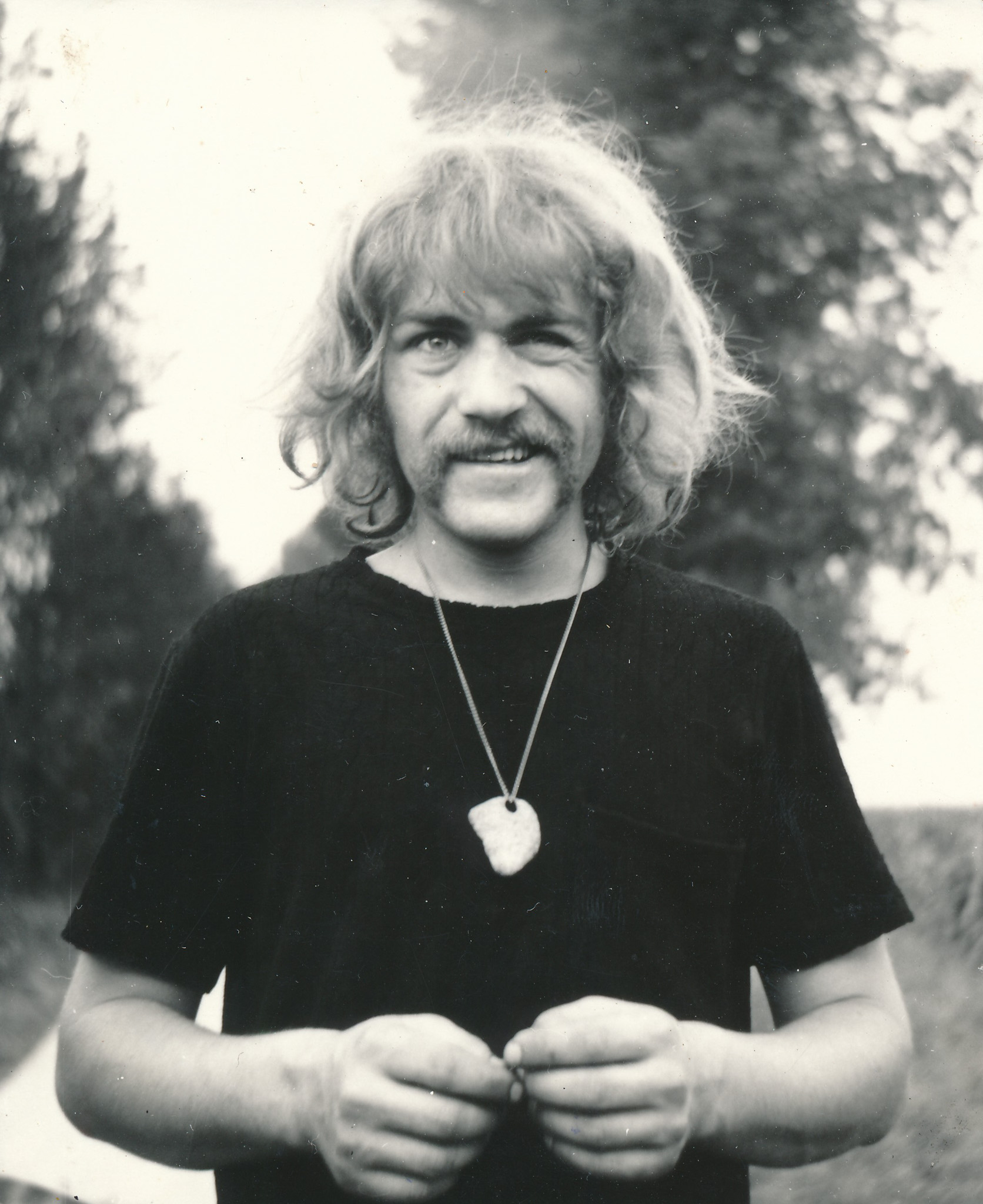

Stanislav Pilík was born on 25 September 1950 in Příbram. His parents soon divorced due to his father‘s alcoholism and he ended up in a children´s home at the age of four due to the new social policy of the Communist Party (first in Jemnice, then in Telč). After four years he was able to return to his family, but he was left with permanent scars - as he says, he remained emotionally „hardened“ compared to his peers all his life. This was not helped by several moves and the arrest of his stepfather, who was very close to Stanislav Pilík, for defaming the Republic: he copied and distributed a speech by František Kriegel critical of the Communist Party. After primary school in Rakovník, Stanislav Pilík graduated from the Business Academy in Resslova Street in Prague and completed several terms of French and Romanian at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University, which he did not finish because of his passion for music and playing in a band. After completing his military service in Rakovník, he worked as an expedition manager in an agricultural enterprise until the revolution. Fearing for his wife and two children, he did not get involved in any way - until 1989, when hope was awakened in him and he became involved in the formation of the Rakovník Civic Forum. After the revolution, he worked for four years as a councillor, later changing several professions before establishing himself as a journalist. In 2024 he was still living in Rakovník.