I was given three lives

Stáhnout obrázek

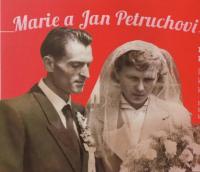

Jan Petrucha was born on 22 June 1924 in Hroznová Lhota. In 1936 he enrolled at a grammar school in Kroměříž, where he experienced the war. In 1943 he was to be assigned to forced labour in Germany, but his father‘s illness allowed him to stay at home to work on the family farm; he had to interrupt his studies. In April 1945 he was shot when the battle front passed through the village, but this did not stop him from returning to school and passing his graduation exams in the summer. In autumn that year he was accept to the Faculty of Arts in Brno to study history and geography. In spring 1948 he and other students from the faculty were pressured to join the Communist Party. This caused him to take up employment as a teacher from September and continue his studies long distance. He was active in the Catholic sports movement Orel (Eagle), where he also distributed pamphlets. In February 1949 he was arrested and imprisoned in Uherské Hradiště. He was convicted of sedition and sentenced to three years in prison in June; he was taken to the uranium mines in Jáchymov. After his release in 1952 he applied to work in the mines; he was drafted into compulsory military service with the Auxiliary Engineering Corps, where he did forced labour. He married in August 1957; he and his wife Marie raised thirteen children. Jan Petrucha died on March 1st, 2022.