I tried to follow the Ten Commandments in order to live my life properly

Stáhnout obrázek

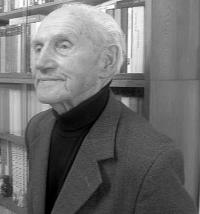

Jaromír Petlach was born September 11, 1924 in the village Obce, which became merged with Ochoz into one village called Ochoz u Brna in 1947. He grew up in a Catholic family and he regularly attended the mass in the local church. He was a member of the Orel sports organization and he was helping his father with work on their family farm. He was supposed to be sent to do forced labour during the war, but he avoided it due to illness. After the end of the war Jaromír began farming again, but the family was affected by the collectivization process in 1948. His father Josef succumbed to intense pressure and he eventually joined an agricultural cooperative. Jaromír Petlach was appointed the cooperative‘s agronomist and later its chairman. He was later expelled from the cooperative‘s management for his criticism of the situation in the cooperative, and he eventually left it entirely of his own accord. He worked in the companies Zetor and Telekom. With his wife they raised daughter Lenka and son Jaromír. Jaromír now lives in his native house in Ochoz u Brna. Jaromír Petlach died on 25 December 2019.