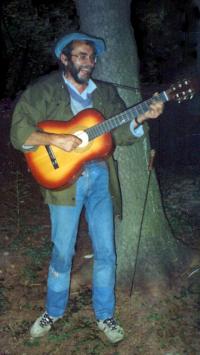

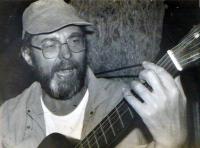

It was a play at freedom

Stáhnout obrázek

Josef Morkus was born on February 5, 1945 in Jihlava. His father was a German and his mother was a Czech. All relatives from the father‘s side of the family were deported to Germany after the end of the war. The Morkus family was allowed to stay thanks to the Czech nationality of Josef‘s mother. After the communist regime‘s rise to power, the Morkus family continued going to church and Josef‘s father was boycotting communist parades and other activities which promoted the new regime. As a result, the authorities turned down his son‘s application for study at a secondary school. Josef learnt the glasscutter‘s trade and he began working in the company Motorpal. At that time he also started going tramping with his friend. In 1983 he began teaching at a vocational school, the same one at which he had studied, and in 1987 he began working as a teacher at a secondary technical school. He eventually earned his school-leaving certificate later after having attended evening classes. In 1989 he signed the manifesto „A Few Sentences.“