And November 1989 … in my opinion, it was a Biblical miracle

Stáhnout obrázek

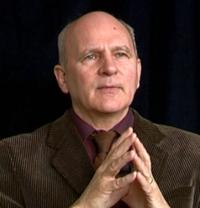

František Mikloško was born on June 2, 1947 in Nitra into a Catholic family. In his youth, he was often a witness to his close acquaintances being taken to prison or otherwise persecuted by the communist regime, what actually made his anti-communist conviction even stronger. After passing the leaving examination at the secondary school of construction in 1966 he started to study mathematics at the Faculty of Natural Sciences at Comenius University in Bratislava. There he met many activists involved in the secret church, especially Vladimír Jukl. He became a member of a religious group and got involved in the structures of the secret church, in the frame of which he used to organise spiritual retreats and build up groups among students. He successfully completed his studies in 1971 when he also started to work at the Institute of Technical Cybernetics of the Slovak Academy of Sciences, where he engaged in numerical mathematics. At the same time he devoted himself to activities of the secret church and he was successful at establishing religious groups among students. The 1970s were a period of quiet work and effort to build up the widest network of small groups possible. He also got involved in various activities of the Fatima community, which was established by several members of the secret church. In 1980s, his activities also included organising mass pilgrimages, which were open anti-regime events. However, these activities of the secret church didn‘t escape the State Security‘s notice. Therefore, František Mikloško couldn‘t avoid being interrogated and monitored. In 1983 he was dismissed from the Slovak Academy of Sciences and he found a job as a labourer. The second half of the 1980s was marked by the decline of the communist regime. In this period, František Mikloško was actively engaged in all the important activities of the secret church; he also intensively participated in preparations for the Candle Manifestation, which was held on March 25, 1988 in Bratislava. He spent the first days of the Velvet Revolution in the courtroom, where he supported Ján Čarnogurský, whose trial was taking place those days. As a representative of the Catholic dissent, he was requested to take part in the movement called Public against Violence, which was being formed at that time. František Mikloško stayed at the top level of politics even in the post revolutionary period. From 1990 he was a member of the Slovak National Council (SNR) and the National Council of the Slovak Republic, where he remained until 2010. In the years 1990 - 1992 he served as a Chairman of the Slovak National Council. In the period of 1992 - 2008, he was a member of the Christian Democratic Movement. Twice he ran unsuccessfully for the position of President of the Slovak Republic.