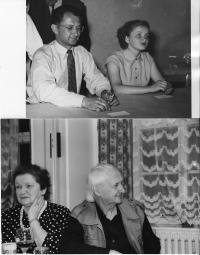

“Mom asked Boris: ‘Well, you have finished the graphic design school, and what would you like to do next?’ He replied that he would like to be in the film business. He had a dream he would be like Disney in America. His mom then read a newspaper and she noticed an advertisement that some company was looking for an animator to do animated films. His mother knew German and she thus translated it for Boris, and he liked it and he wanted to get there very much. They went there immediately. The company was located in Francouzská Street, near Wenceslas Square. My husband came there, knocked on the door and the door opened and a man came out and started speaking in German. Fortunately Boris’ mom, who was with him, understood him, because she had attended school during the Austria-Hungary era and she had thus learnt German and she could speak it really well. She thus explained to the man that her son was deaf and that it had been his lifelong dream to work as an animator for animated film. The man said: ‘Fine, but can he draw?’ Mom said: ‘Yes, he can, he studied a graphic design school, and his drawing is excellent.’ The man thus invited them in. They came to a room where there were many desks. My husband was the first candidate who came there. He was looking at his desk, which had a slanted surface with a glass on the top, just like the desks for artists look like. There was a stack of papers on the desk and they told him to draw a little girl and make her walk and move. My husband looked startled for a while; he didn’t know what to do. But the man told him to calm down and said that he should just take his time and that he had the whole day to do it. The man and Boris’ mom then left. My husband was sitting there and thinking. Suddenly he got an idea, he remembered those little stacks of paper with picture frames, you know what I mean – if you thumb through them quickly enough, it looks as if the pictures are moving. My husband remembered this and he tried to draw the little girl taking the first step. He didn’t know how large it should be, but he tried it. Then he went through the stack of papers to check it, and he found out that it didn’t look natural, and that her steps were too long. He thus crumpled the used papers, threw them to a waste paper basket under the desk and he began anew, but he didn’t like it either, and he crumpled the papers and threw them away again, and gradually the stack of papers on the desk was diminishing but the waste paper basket was overflowing. He eventually discovered that he needed to draw small sections at a time so that the movement would look fluid and natural. The girl’s body needed to move as well, because otherwise she would look like a puppet with only legs moving. As he was drawing it over and over again, he learnt it and understood what to do. When the man from the company came to check upon him, he praised him a lot: ‘Schön! Gut!’ (My husband understood this, because he knew a little bit of German). The man immediately assigned other work to him. Boris’ mom was happy that he was so successful and that the company hired him. But at the same time they were looking for other new employees. My husband remembered his two brothers, who were without a job at that time, because the Germans had closed down their schools and they had nothing to do. It occurred to him that they might join the company, too. His older brother was an excellent photographer and he knew how to shoot films and operate a film camera, and the eldest brother spoke perfect German and he was thus able to communicate with the boss about work-related matters. The boss was giving them assignments, and my husband’s eldest brother was searching for people who were needed for it, and my husband was teaching them how to animate the motions of the characters, and the other brother was teaching the people how to operate a photo camera and a film camera so that they would know how to create various kinds of films. I have the names of their first films written here. I remember that the third film was called Wedding in the Coral See. My husband kept records of everything and the films were really beautiful. Apart from that, my husband was also drawing various comics and pictures for magazines. But back to the film studio: in 1944, when the end of the war was near, one day the studio manager didn’t come to work. He used to come there regularly to check the work progress and to see what the people were doing. At that time there were already about fifty people working there. They were all sitting by their desks, my husband was teaching them what and how to draw, and his older brother was shooting the individual frames with the camera, and the eldest one was organizing the work, but one day the manager didn’t come to the studio. Nobody knew what happened or what to do. At that time they just finished the film Wedding in the Coral Sea and it only needed to be delivered for screening, but they didn’t dare to do it without the manager. They were a bit confused, and they waited for two or three more days, but manager didn’t show up. They had a meeting and they agreed that they would make a request to the committee and ask whether the studio might be allowed to continue if they would manage it themselves. The committee approved of it, but they needed to find a new name for the studio. They were raking their brains about it. It was called a film trick studio, but they didn’t like the name. They were thinking how to include the work ‘trick’ in the name. Then they got the idea that the studio was actually managed by three brothers. And thus the name Bratři v triku (‘Brothers in T-shirts’ – a pun on T-shirt and trick, which sounds the same in Czech – transl.’s note) was invented. Then they asked Mr. Trnka to create a logo with three little boys for them. Mr. Trnka was the author of the three boys in striped T-shirts who take a bow. When the logo was finished, they sent a request for authorization of this studio to the committee, and the committee approved it, of course, because it was the first Czech studio for animated film, and they were happy about it as well.”