It was an act of revenge on my family

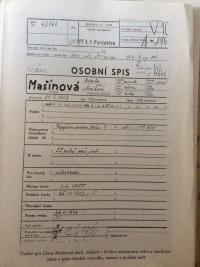

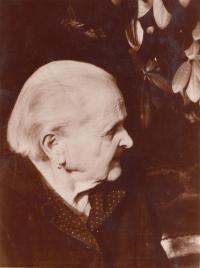

Zdena Mašínová was born on the 7th of November, 1933. She is the daughter of the resistance hero Josef Mašín, and the sister of the anti-communist fighters Ctirad and Josef Mašín. After her brothers fled in 1953 and her mother‘s arrest and subsequent death, the handicapped Zdena Mašínová had no family left. She spent a month in communist custody therefore, she did not take part in her brothers‘ resistance efforts. Her entire life, she was persecuted by the regime, the only work she managed to get was washing laboratory glassware. She blames the post-November society of being morally decrepit -- according to her, the dissent was not at all prepared to lead the country into democracy. She took an active interest in the case of Vladimír Hučín, who was arrested multiple times for spreading anti-communist propaganda. She received part of her family‘s property through restitution agreements.