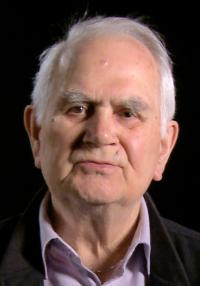

After the communist coup, I believed the Americans would come and liberate us

Stáhnout obrázek

Zdeněk Mandrholec was born on 1 April 1930 in Přerov. After his father‘s death, the family had to move out from a company-owned apartment. He, his mother and sister then moved to western Bohemia. He graduated from a business school and worked at a wool combing factory in Nejdek. He showed his discontent with the communists taking over power in February 1948. In 1951 he had to start compulsory military service. He was annoyed by training to fight for a regime that he hated. He served on a unit placed in a former monastery in Nová Říše from which the monks were driven out. Along with other soldiers he established a group which prepared itself to fight the communists. They believed that the US army would come to help, as it did during the liberation from Nazi Germany. However, their group was uncovered. In 1953 he was arrested and sentenced to ten years in prison for high treason. He spent six and a half years at uranium mines in the Jáchymov area. In 1960 he was released on an amnesty. Then he worked in a blue-collar job at road construction where he stayed up until retirement. Only after 1989 did he find out who turned their group in in the 1950s. Zdeněk Mandrholec died on June 13, 2023.