It was too hard to oppose the regime

Stáhnout obrázek

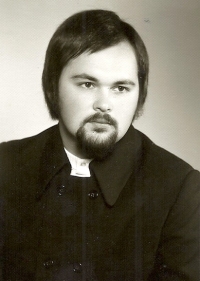

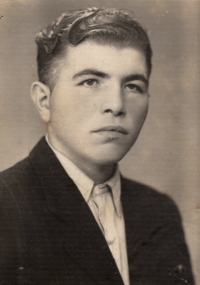

Josef Londa was born on 21 March 1951 in Paseka near Šternberk. His parents, Anna and Antonín Londa, had already gone through one marriage during the World War II and lost their partners under dramatic circumstances. Antonín Londa was tried in 1944 for the unallowed slaughter of a pig in Kounicovy‘s dormitory in Brno and from there deported to the Buchenwald concentration camp. His brother Tomáš and Josef’s first wife Eliška were arrested by the Gestapo in January 1945 because the family was helping partisans in the meadows near Hošťálková. Both of them disappeared without a trace behind the gates of the Kounicovy dormitories. Josef‘s mother Anna was one of the Volhynian Czechs who were to be taken to the gulag as kulaks by the Stalinist regime. Thanks to the 1946 repatriation agreement, Anna was able to return to Czechoslovakia, free of all her possessions, where she met Antonín Londa in Paseka near Šternberk and together they started a family. Their son Josef grew up on the farm, which in 1956 the family had to hand over to a unified agricultural cooperative. After his application to the secondary industrial school in Olomouc was rejected, he was trained as an electrical fitter at Uničovské strojírny. On 21 August 1969, on his way back from an assembly plant in northern Bohemia, he accidentally found himself in the middle of a demonstration on Prague‘s Wenceslas Square. In order to complete his secondary education, he joined the Communist Party as a candidate during the 1970s under pressure from his superior. During the Velvet Revolution in 1989, he actively participated in the proliferation of leaflets and the preparation of the general strike. Josef Londa was living with his wife Ludmila in a family house in Šternberk in 2021.