I had an urge to fight the system

Stáhnout obrázek

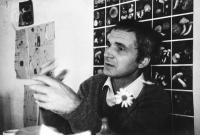

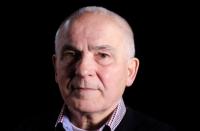

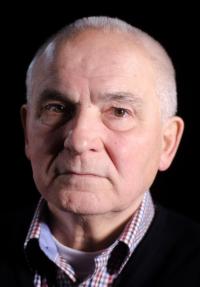

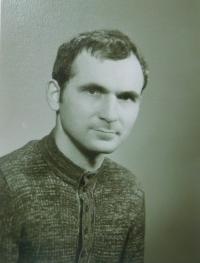

František Lízna was born in 1941 into the strongly Catholic family of a farmer from Jevíčko and a Sub-Carpathian Ukrainian. From his early childhood he was a sworn anti-Communist who felt the urge to fight against the system. He was arrested and imprisoned for seditious activities on several occasions - for the first time in 1960 for destroying a Soviet flag, in 1964 for attempting to leave the country, in the late 1970s and in the years 1981-1983 for distributing samizdat literature, and finally in 1988 for printing pamphlets about political prisoners. From 1968 he was employed as a social worker in Velehrad, where he felt the calling to join the Society of Jesus. After completing studies of theology he was ordained to the priesthood, but he was not given state permission to provide spiritual services. Between his prison stays he worked in various places throughout the country in social and health services while actively participating in dissident efforts surrounding Charter 77. He is a recipient of the Order of T. G. Masaryk for outstanding contributions to the development of democracy and human rights. František Lízna died on 4 March 2021.