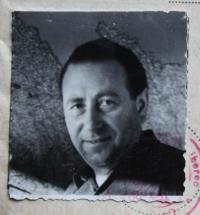

The communist membership card saved my life

Stáhnout obrázek

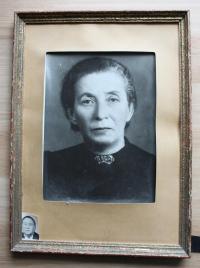

Josef Lesný was born in 1911 in Hungary as Jozef Lövinger. He was born into a mixed Jewish-Christian family and studied to be an artist of cabinetry. In the 30‘s, he joined the pre-war communist party in Bratislava. He was called to arms in 1938 and served as a machine-gun operator. He was drafted once again during the war and as a half-Jew born in Hungary, he served in a labour unit of the Hungarian army. He was captured by the Red army, his pre-war communist party card saved his life and provided him with better treatment in a detention camp in the Soviet Union. He underwent parachute training in Petropavlovsk and was seeded as a member of the Red army to the battle of Stalingrad. Later, he asked for a shift to the Czechoslovak unit and served in the 3rd brigade, taking part in combat at Jaslo and Dukla. He was injured. Since the war, he has lived in Liberec. He has died 7th October 2011 in the age of 100 years.