I got Czech citizenship, so I feel at home here

Stáhnout obrázek

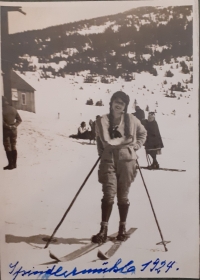

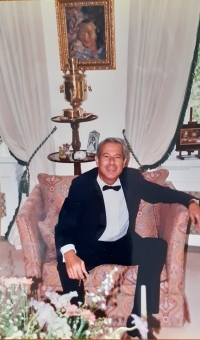

André Lenard was born on 21 February 1940 in Paris. His mother was Czech Helena Lenard from the famous Vizovice family of slivovitz producer Rudolf Jelinek and his father was Polish doctor of economics Roman Lenard, who died at the very end of the war. One of the first repatriation trains took André and his mother back to Vizovice in October 1945, where André started first grade. Although he quickly learned Czech, made friends and got used to his new surroundings, he and his mother moved again in 1949. Jelinek‘s distillery was nationalized and they had to move out of the apartment above the factory. Mum was born and lived her young years in Bratislava, so they went there. André graduated from high school in Bratislava and moved to Paris. He had to learn French again, find his place in a new environment and start working. After some vicissitudes, he managed to join the prestigious French bank Paribas, and since he spoke several foreign languages, his entire professional life as a banker was devoted to contacts with Eastern European countries. In the 1970s he worked in Moscow, returning after three years to represent various international banking houses. In later years, when he was already a freelancer, he was involved in financing hotels in Prague and Bratislava. In 2023 he lived alternately in France and Prague. In March of the same year he obtained Czech citizenship.