They arrested me when we went with the orchestra to play at a celebration of Stalin’s birthday

Stáhnout obrázek

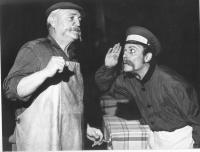

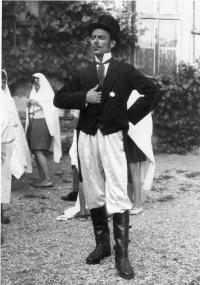

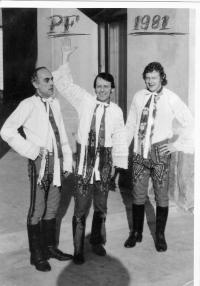

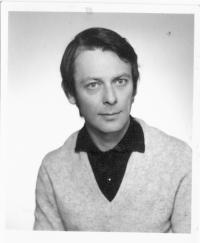

Milan Kolář was born in Valtice in 1933. His father was cobbler, his mother tended to their home. The Kolářes were one of the few Czech families to remain in the formerly Austrian town of Valtice after 1938. Milan attended German schools and he was also a member of the Hitlerjugend. He remained in Valtice throughout the war, the liberation, the expulsion of Germans, and the resettlement. After the war he started grammar school in Břeclav. In autumn 1948 he was approached by two youngsters from Brno, who asked him to help them cross the state border in Valtice. Milan Kolář complied to their request, but after a short while the boys returned to Czechoslovakia. Milan was arrested and held in custody in Brno for fifty days. He celebrated his fifteenth birthday in prison, and then Christmas and New Year‘s Eve. After being released he studied at the faculty of education in Brno, and after graduating he taught in various border villages before obtaining a permanent position at the school in Valtice. When the normalisation began, he stirred up a number of conflicts at the district party meetings, which nearly cost him his job. Throughout his teacher‘s tenure he founded amateur theatres, singing clubs, and choirs, in which way he played a fundamental part in developing the culture of Valtice and the surrounding area. Dien in 2015.