To overcome one‘s fear when I served as a courier to Poland was a major test in my life

Stáhnout obrázek

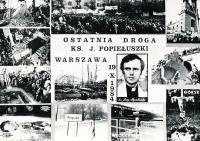

Ewa Klosová, née Głowacka, was born on March 26, 1956, in Poznan. Her father worked as a technologist, her mother was a sourcing manager. Although they belonged to the middle class, due to a general shortage in Poland they struggled to make a living. Ewa’s parents could not even afford to pay for her education. She studied animal husbandry in Poznan and in 1978 joined the agricultural cooperative in Krosno. After two years she was forced to leave her position, since she criticised poor work of her manager. In 1979 she joined a company specialising in procurement and sale of animal skins and in 1980 actively joined the Solidarita movement. A year later, a state of emergency was declared in Poland and Solidarita was pushed underground and it disappeared from Ewa’s life. In 1984, during a trip to Prague, she met her future husband Juraj Puci, they married in 1985 and next year she moved with him to Czechoslovakia. She worked in an experimental institute, where she took care of test animals. It was here she met her colleague Anna Šabatová, her husband Petr Uhl and started illegally working on translation of Infochs to Polish and also worked as a courier for Polish-Czech Solidarity. In 1989, for instance, she prepared ground in Poland for the escape and hiding of the Czech dissident and hunger-striker Stanislav Devátý, who was, repeatedly, sentenced to prison and whose life would have been threatened by another hunger strike. In 1989 she took part in the Festival of Czech Independent Culture. When her marriage broke up in 1993, she married the journalist Čestmír Klos. She worked with the East-European Information Agency (VIA) and the Polish Institute in Prague.