But there was the State Security department above us I had never been up there but I heard screaming, painful screaming coming from there I heard it almost every night when I was on night duty

Stáhnout obrázek

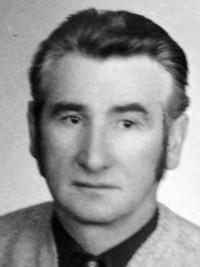

Jan Klimas was born in the village Fokušová in Slovakia on February 2nd, 1924. He moved to Prague where he served his time of apprenticeship and experienced the Prague uprising in 1941. After the war he joined the National Security Corpse in Štěkeň in1946. He served with frontier-guard in South Bohemia in 1947-1949. He spent the February days 1948 in Prague. He worked with National Security Corpse again in 1949-1954. As a police member he experienced violent interrogation and agriculture collectivization. He filed a complaint about a Strakonice-police officer for abuse of authority of a public agent for violent collectivization. However, he was unsuccessful due to normalization. He worked in the Ceska Zbrojovka armory in Strakonice and then at the Lake Lipno.