The Armaments Factory was sold off and stolen off, mainly stolen off

Stáhnout obrázek

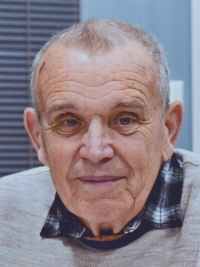

Josef Kaše was born on 16 October 1938 in Koloveč, Domažlice. His father, Jan, ran his own pottery business, and his mother, Marie, took care of the small family farm and household. Josef remembers the bombing of Pilsen, fifty kilometres away, and the arrival of the American army. In the nineteen-fifties, he graduated from the Vocational School of State Labour Reserves (OUSPZ) on the premises of the Plzeň Škoda Works (then called Vladimir Ilyich Lenin Works), where he started working after his apprenticeship. During his compulsory military service in Brno (1957 to 1959), he met his future wife Dagmar, whom he moved to after leaving for civilian life. In Brno, he began to work at the Armaments Factory (Zbrojovka). He stayed there for almost forty years until his retirement at the end of the nineteen-nineties. From his position as an electrician, he was in charge of the so-called technical operation of production (TOV) at the Armaments Factory. Around 1980, he joined the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ) under pressure. After the Velvet Revolution, he changed jobs within the Armaments Factory and worked in boiler maintenance until his retirement. In 2023, Josef Kaše was living in Brno.