To not live in a coffin

Stáhnout obrázek

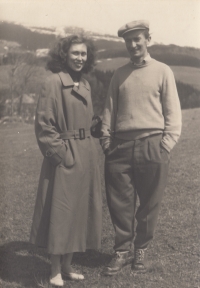

Milena Kalinovská was born on April 24, 1948, in Prague into a bilingual family of Russian emigrants. After the occupation of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact troops, she emigrated together with her fiancé Jiří Studnička to Great Britain, where she studied and later ran the Riverside Studios. She became the world‘s leading gallerist and curator, working in Boston and New York, and until recently also in Prague. She was the only Czech person to be nominated for the Turner Prize for her artistic contribution. For three years she worked in the narrowest management of the National Gallery in Prague.