They wouldn‘t let him go to sea, he sailed down the river. And finally he escaped

Stáhnout obrázek

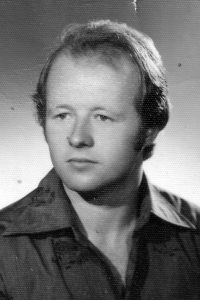

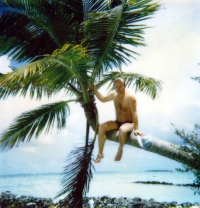

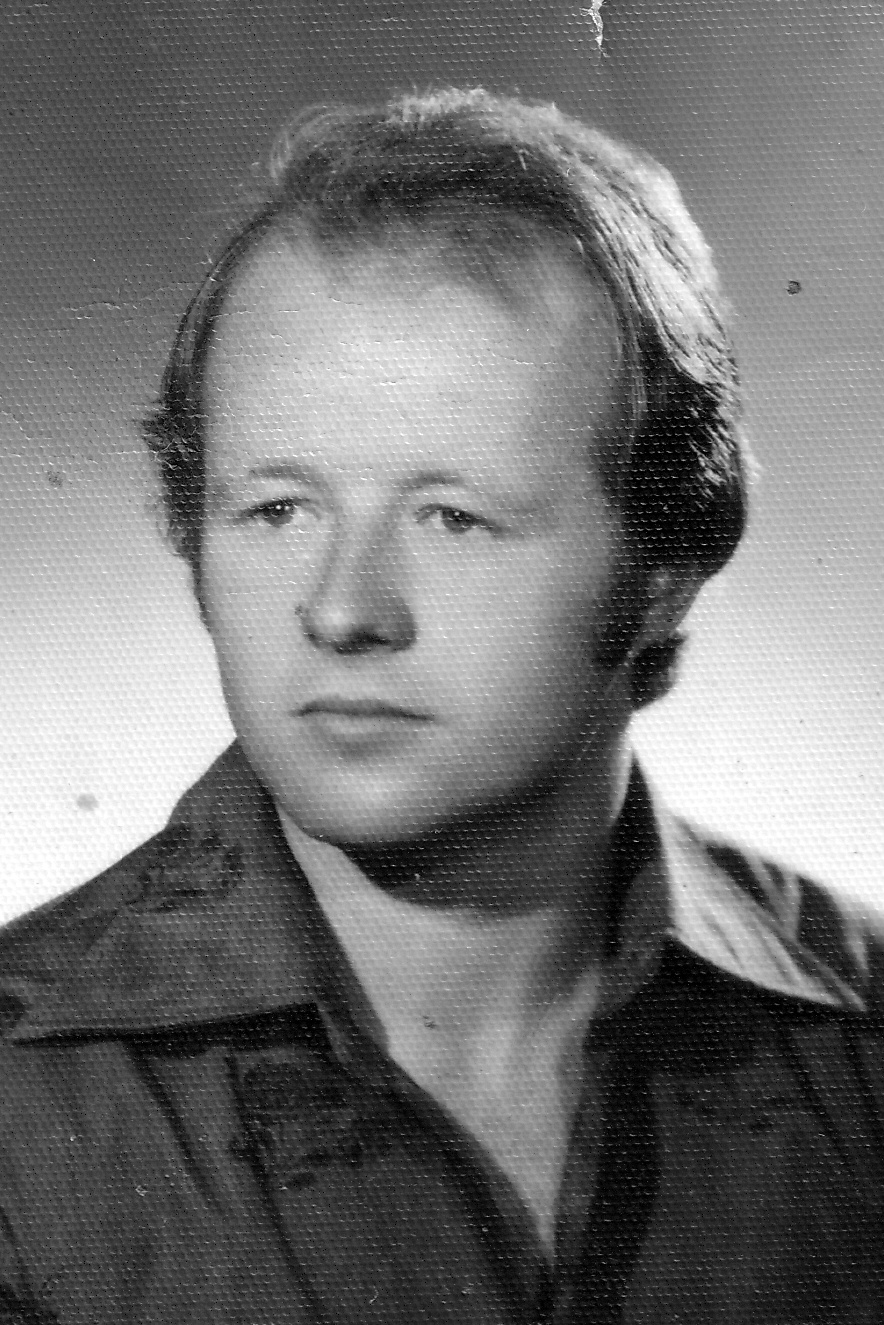

He was born on 13 May 1952 and grew up in Bolatice in the Hlučín region. His father, Herman Jiřík, had to enlist in the Wehrmacht after the outbreak of World War II, fell into Russian captivity and returned in 1946. Since childhood, Karel Jiřík longed to travel and planned to become a sailor and sail the seas. He apprenticed in Ostrava as a locksmith. In 1968 he was active in the Union of Students and Apprentices, which was banned at the beginning of the normalisation after the August invasion. He repeatedly applied for a job at the Czechoslovak Shipping Company, but was always rejected. In 1973, he started working for the Czechoslovakian Elbe-Odra shipping company, sailing on the Elbe from Hřensko to Hamburg. State security forced Karel Jiřík to cooperate, but he did not cooperate and emigrated to Hamburg in 1981. He lived in Frankfurt am Main, where he earned his living as a taxi driver, and after 1990 he returned to Czechoslovakia and started his own business. At the time of filming in 2023, he was living in Opava.