Meetings of Polish and Czech dissidents at the border were not picnics

Stáhnout obrázek

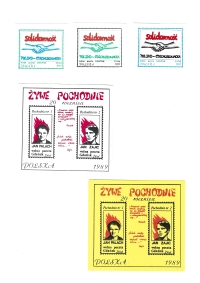

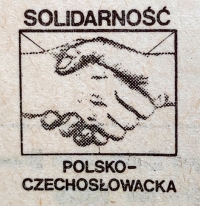

He was born on 12 November 1960 in Bolesławiec, Lower Silesia, and after graduating from high school he went to study Polish studies and art history at the University of Wrocław. After the formation of Solidarity, he became involved in the Independent Students‘ Association (NZS). After the declaration of martial law in Poland on 13 December 1981, he hid for two months from the threat of arrest that threatened both Solidarity and NZS activists. In January 1982 he joined the underground structures, and from February 1982 he took over the leadership of the Polish-Czechoslovak Solidarity group - he organised the exchange of information between Polish and Czech dissidents and three large secret meetings of the main dissidents at the border. In April 1987 he took part in a public protest in Wroclaw against the imprisonment of Petr Pospíchal, an activist of Charter 77 and Polish-Czechoslovak Solidarity. From December 1987, together with Jarosław Broda, he published the Newsletter of Polish-Czechoslovak Solidarity, and in April 1988 he launched the Patronat appeal in support of political prisoners. In April 1989, he was at the origin of the idea of organising an international seminar on Central Europe, which took place in Wrocław on 3-5 November 1989, together with the Review of Czechoslovak Independent Culture. In 1990-1991 he was a political advisor at the Polish Embassy in Prague and then the Duke of Wroclaw. In 1994-2001 he worked as a writer and director of documentary films, in 2001-2007 he was the director of the Polish Institute in Prague, and then in supervisory and advisory positions at ORLEN Unipetrol. From 2012 to 2021 he was the head of the City Gallery in Wrocław. From 30 November 2021 to 31 January 2022 he was the Ambassador of the Republic of Poland to the Czech Republic. He is the recipient of numerous Czech and Polish awards and orders. In June 2023 he was the director of the Municipal Gallery in Wroclaw, where he also lived.