The Legion made me a man, it helped me a lot

Stáhnout obrázek

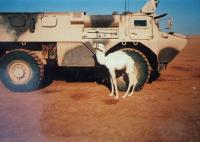

Antonín Hruška was born in a Communist official family in 1946. His father studied in Moscow between 1952-1955. Antonín Hruška wanted to be a soldier since his fifth school year. He decided to study at military high school in Poprad. He graduated in 1965, was a lieutenant at 20 already and started a service with signalmen at a general staff in Prague. In 1968 he engaged in the social changes of this year, he for instance pasted up posters against the Soviet occupation. He was dismissed from the Army during the vetting in 1969. He was sentenced to 18 months for assaulting a policeman (National Security Police Force member) during a road checking. After his release he decided to emigrate (1974). He fled with a friend via West Berlin to West Germany first. After half a year he joined the Foreign Legion in France. He was assigned to paratroopers with whom he took part in various actions including those in the town of Kolowez in the separatist province Katanga (Shaba) in Zair (Democratic Kongo) in 1978. He got wounded during a parachute jump in Djibouti in 1982. Having been cured he did not come back to paratroopers. He served with motorized infantry. He served at bases including Mayotta or French Guyana in the ‘80s. Towards the end of his career in the Foreign Legion he took part in operations in Kuwait and Iraq in 1991. He moved to the Czech Republic in the ‘90s. He lived in Vižňov at Meziměstí in the Broumov area. Antonín Hruška died on October 13, 2010.