Like a snail that knows how to crawl on the edge of a razor blade.

Stáhnout obrázek

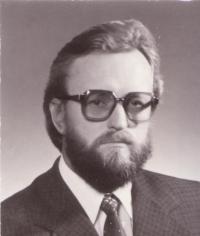

Ing. Tomáš Hradílek was born in 1945 in Lipník nad Bečvou. The turning point in his life came in the 1960s, when he was studying at the University of Agriculture in Brno. In 1966, he joined the Communist party and became affiliated with its reformist wing. In 1969, after the invasion of the armies of the Warsaw Pact into Czechoslovakia, he left the party. In 1977, while listening to the „Voice of America“ broadcasting, he learned about the Charter 77 and immediately went to Prague to sign it. This cost him his job in the JZD (jednotné zemědělské družstvo - Agricultural Production Comradeship) in Týn and he became a sawmill worker. He was also involved in the activities of the Charter movement and became a member of the association of spokesmen of the region of northern Moravia in the 1980s. That‘s how he was targeted by the secret police. They installed a bugging device in his house and he was arrested several times. He co-authored an important document called „A Word To Our Fellow Citizens“. This document was supposed to mobilize the people to act against the totalitarian regime. In order to inspire his fellow citizens, he acted as a role model and took part in a number of very risky undertakings. Together with Rudolf Březina, he co-authored an open letter calling for the resignation of Gustáv Husák. They also filed a criminal charge for high treason against Vasil Biľak. Last, but not least, they came to the First May Parade in Olomouc with a banner saying „The Charter 77 calls for civil courage“. All these actions received coverage by western media agencies and were broadcasted to the West. In January 1989, Mr. Hradílek became the spokesman of the Charter 77 and further intensified his activities against the regime. He became the co-founder of the Movement for a civil society and the Society of the friends of the United States of America. After the student demonstrations on the Národní třída (the National Avenue in Prague) in November 1989, he co-founded the political platform „Občanské fórum“ (Civic Forum) in Olomouc and in Prague and became one of the leading figures of the revolutionary days in problem-ridden Ostrava. In December 1989, he was among the first twenty deputies that were co-opted to the Federal Assembly and he became one of the deputies who elected Václav Havel for president on December 29, 1989. In June 1990, he became the minister of the interior but he resigned after just five months in service for physical exhaustion. He continued to be a member of the federal parliament till 1992. Today, he is in retirement and fully indulges in his life-long hobby, breeding aquarium fish.