If only we could also lead such heroic lives

Stáhnout obrázek

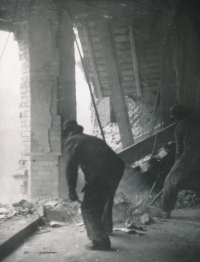

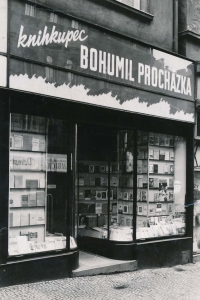

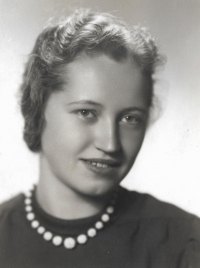

Marta Holeková was born in Prague on 22 March 1947 into the family of Bohumil Procházka, a bookseller. At the outset of World War II, her father joined the resistance, working with the Faithful We Stay Petition Committee; when he was discovered, he was incarcerated in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp for four years. Her mother Lydie Pravda Procházková came from the family of Josef Štifter, a preacher of the Unity of Czech Brethren. During the war, they maintained friendly relations with the family of the Jewish architect Rudolf Wels, and they hid their belongings for safekeeping when the Welses were imprisoned in Terezín. Although most members of the Wels family died in Auschwitz, Marta Holeková is still friends with their descendants, who live in Great Britain. Her father’s bookshop was nationalised in 1950, and Marta and her sister grew up in relative poverty. While in her first year at grammar school in 1963, Marta was badly shaken by her father’s death. After graduating, she completed a follow-up course in librarianship. During the summer holidays of 1967 and 1968, she worked as an au pair in Great Britain, where she received news of the Warsaw Pact forces’ invasion of Czechoslovakia. She refused the option of emigration, choosing instead to help her homeland by distributing Christian literature inside totalitarian Czechoslovakia. From 1970 to 1989, she worked with the Dutch Christian organisation Open Doors; she picked up parcels of books from abroad in Prague and helped deliver them to readers. She was later aided in this activity by her husband Pavel Holeka. Both of them were active members of the Church of the Brethren (formerly the Unity of Czech Brethren). During the normalisation period, she was employed as a librarian at the Department of Russian Studies of the Faculty of Arts of Charles University in Prague. She gave birth to two children, Matouš and Noemi. After 1989 she began teaching English at a primary school but fell seriously ill soon after. She resumed work in 1996, this time as a specialist at the foreign section of the Rectorate of Charles University and later as a librarian at the Institute for Criminology and Social Prevention.