Sir Commander, there is God!

Stáhnout obrázek

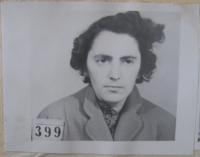

Antonie Hofmanová was born into the family of a weaver and a small farmer in the sub-Krkonoše village Horní Branná on June 13th, 1923. She studied at the Secondary School of Economics in Prague during WWII where she came into contact with Catholic youth clubs. Under this influence, she decided to become a catechist. She taught religion in the post-war border area and kept deepening her spiritual activities in terms of Jocism clubs. She contacted members of the Catholic Family, especially Silvestr Krčméry. She was arrested in December 1952 and, about a year later, she was sentenced in the trial ‚Hofmanová and comp.‘ She was sentenced a six-year imprisonment. After two and a half years she was released for health reasons. She returned to the sub-Krkonoše region. After a strenuous job hunt she eventually became a nurse in Janské Lázně. She continued to organize illegal Christian meetings. Antonie wrote multiple books including one about her life: Žijeme jen jednou (We Live Only Once). She died on June 16th, 2009.