Forgiveness is natural

Stáhnout obrázek

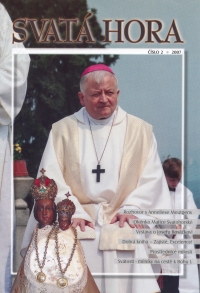

Mons. Karel Herbst was born on 6 November 1943 in Prague. In 1960 he trained as a mechanic of electric lokomotives and he worked in this job for eight years. At the same time he completed a grammar school in Prague. In 1968-1973 he studied at the Sts Cyril and Methodius Faculty of Theology in Litoměřice. He was ordained to priesthood on 23 June 1973. In 1973-1974 he acted as a chaplain in Mariánské Lázně, in 1974-1975 he worked at the Holy Mountain pilgrimage site near Příbram. On 6 January 1975 the state approval to perform religious services was taken away from him for omitting to read one sentence from a Christmas pastoral letter. The sentence mentioned the celebration of the 30th anniversary of the Soviet liberation of Czechoslovakia. From February 1975 to August 1986 he worked at the state cleaning company (Úklid) as a shop windows cleaner. In the mid-1970s he became acquainted with the Salesian community activities, and on 11 September 1976 he took his life vows in the congregation of the Salesians of Don Bosco. In 1974-1986 he actively organised Salesian „cottage stays“ - holiday events for children within the framework of underground Salesian activities. From September 1986, when he was given back his state approval, to 1989, Karel Herbst served in Staré Sedliště in Tachov District. In 1990 he was the parish administrator in Všetaty. From 1990 to 1997 he was the director of the Salesian community in Prague-Kobylisy and administrator of the local parish. In 1997-2000 he held the post of spiritual director of the Archiepiscopal Priestly Seminary in Prague-Dejvice. From September 2000 to March 2002 he was the parish administrator in Fryšták near Holešov. On 6 April 2002 he was appointed auxiliary bishop of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Prague and titular bishop of Siccesi. He resigned his position in 2016 and became auxiliary bishop emeritus.