How was it possible that three bums could just walk into your farm and say: In the name of the people we confiscate this farm

Stáhnout obrázek

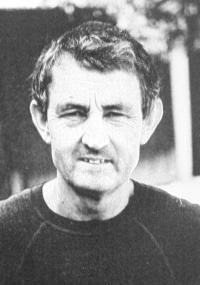

Jindřich Hašek was born September 6th 1934 in an agricultural village of Úhonice in the Prague-West district. His father, Jindřich Hašek Sr., was a farmer and as an owner of 23 hectares of land, he was marked as a kulak (a village rich) in 1951, arrested and imprisoned in Prague. The Hašek family‘s farm was confiscated to be used by the Unified Agricultural Cooperatives. After his release from detention his father was only allowed to work in ore mines. Jindřich Hašek Jr. attended a secondary school of agriculture, from which he was however dismissed after the completion of his second year in 1952 during the so-called ´purging of agricultural schools of kulak children.´ Together with other similarly affected farmers´ children he went to work at the State Farm Studnice in the Osoblaha region for over a year. The farmers´ children did all types of agricultural work there, and so-called ´ideological evenings´ also formed part of their reeducation. After leaving Studnice, Jindřich Hašek joined the army; he also spent six months working in coal mines in the Ostrava region. Only the fall of the Communist regime in 1989 made the return of private entrepreneurship possible. The administrative process for restitution of property was swift and uncomplicated, and in 1992 Jindřich Hašek and his wife began farming on their land in Úhonice again. Former children of kulaks, who began to call themselves ´Green barons,´ still meet regularly.